Over the past few years, I’ve released numerous videos and social media posts about hip pain during squats. Why? Because it’s a problem I’ve personally dealt with (and overcame) and it’s a problem that I help people frequently tackle.

Out of all the issues I hear from barbell athletes, hip pain during squats seems to be one of the most frequent..and rightly so. It’s frustrating and can often linger for months and years if it’s not optimally managed.

So, I decided to finally put all of my thoughts in one location, this article. If you’re someone dealing with hip pain during squats, after reading this article you will have a solid idea of how to finally overcome it. Let’s get to it!

Why Does it Happen?

Pain, as always, can never be dwindled down to one “single cause” simply because there’s so many factors that can influence your pain! So we can’t really say for sure if hip pain during squats is “caused” by one thing or another. Factors such as stress, anxiety, bony anatomy, programming, and/or form can all play a role!

Instead of focusing on trying to find that one magic bullet “cause” or “diagnosis,” I often try to explain to people that we should switch the approach to treating the symptoms instead. This gives you something tangible to work with vs. being told that the “cause” of your pain is something that’s unable to be changed.

But I have FAI…I’ll never squat pain-free again!

If I had a nickel for every time I hear this…I’d be rich! And to be honest, I don’t blame my patients for it. I blame the medical professionals who have erroneously told them this.

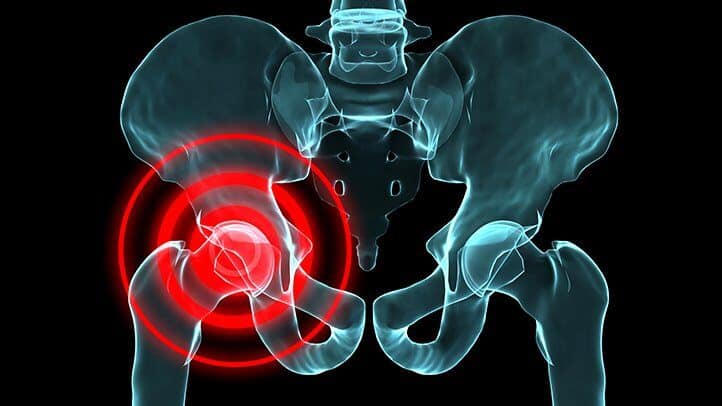

FAI, or femoroacetabular impingement, is a condition where a little extra bone either grows on the head of your femur (called a CAM lesion) or on the rim of your hip socket (called a pincer lesion).

These are big scary words, that people are often told they have after receiving their MRI results of their hip. This is then usually followed up by the medical professional telling you that you shouldn’t squat deep ever again or it’ll only make it worse, and that surgery is your only option to rid your pain. Sigh.

Well here’s the truth. These CAM and Pincer “deformities” are actually quite common in people who don’t even have hip pain. One study shows a 37-55% prevalence of a CAM deformity in asymptomatic young athletes, and a whopping 67% prevalence of a Pincer deformity (1). At this people, with such high numbers, can we even call it a “deformity”?!

If it’s possible for this many people to have FAI without pain, it’s possible to CHANGE your pain despite having this. I’m going to show you EXACTLY how to do this, but first, let me show you what NOT to do.

What NOT to Do for Hip Pain During Squats

When someone comes to me with hip pain during squats, I often have them stop doing the 3 things listed below. Why? Because if these things worked, they probably would have worked by now and you wouldn’t still be hurting.

Don’t stretch your hip flexors

This is many people’s first line of defense. Your front of your hip hurts so why wouldn’t try and stretch it out? The problem with this is that you’re not in pain because you hip flexor is “tight”. The hip flexors are actually on slack at the bottom of the squat, so this doesn’t really even make sense. Often times stretching out the painful area can just exacerbate the issue.

Don’t aggressively try to increase your hip internal rotation

This is a big one. Many people that have hip pain during squats DO have a hip internal rotation deficit on the affected side. But then they forcefully (and often painfully) try to improve their internal rotation. The problem with this is that mobilizing into internal rotation often reproduces the exact pain you feel at the bottom of the squat and it doesn’t cause any permanent improvements in mobility either.

I’ve worked with far too many people who actually stay flared up from aggressively mobilizing into internal rotation, when most likely their symptoms would have calmed down a long time ago if they just stopped doing this.

The truth is you don’t need to “normalize” your internal rotation mobility to squat deep and pain-free. If a drill is reproducing the “pinch” you feel at the bottom of the squat, it’s probably not a good drill for you.

Stop beating the heck out of your hip with a lacrosse ball.

Oh soft tissue work. It gives us that oh so gratifying temporarily relief. The only problem is that it’s temporary, and it’s often counterproductive. You can’t cause true structural change with soft tissue work, so digging into the painful area harder isn’t going to do much other than constantly remind yourself that you have a painful hip.

If you’re someone who has hip pain during squats and you’re endlessly performing soft tissue work, I’d recommend stopping. Now that you know what not to do, let’s talk about what you can do!

Step 1: Optimize Form and Programming

The first step you should do if you have hip pain during squats, is to make sure your form and programming is optimized. While it is true that the human body is very capable of adapting to many different ”forms” and everyone’s squat is going to look different, there should at least be some prerequisites.

For example, if you’re going into a significant amount of knee valgus and hip internal rotation at the bottom of your squat, AND you have hip pain, this is probably something you should fix before we try anything else.

Now let’s talk programming. Often times when I’m working with someone who has pain during a lift, I look at the current RPE (rate of perceived exertion) of their working sets.

Are you consistently training in the RPE 9-10 range? If so, this may be the perfect time to lower the load to an RPE 6-7 to see if this helps mitigate symptoms. Once symptoms calm down, you can slowly build back up from there.

I ALWAYS recommend optimizing form and programming as the first line of defense when pain is involved. No amount of soft tissue work, foam roller, or hands on manual therapy can fix a form or programming error!

Step 2: Change the Modifiable Factors

If you still have pain after optimizing form and programming, it’s time to change something else about the lift. I call these modifiable factors, and they can include

- Stance width

- Degree of toe out

- Tempo

- Depth

- Bar Position

Sometimes all it takes to squat without hip pain is moving your stance in or out a few inches. This can help offload the sensitized tissue and allow you to still achieve a training effect.

Another change you can make is tempo. Simply slowing down the lift is a great way to mitigate symptoms. Many times people with hip pain during squats dive bomb into the bottom position, and as soon as we slow things down, symptoms reduce.

If changing stance or tempo doesn’t work, you can try altering your squat depth. To do this, you can perform box squats to a depth that is right above where it starts to hurt. This way you can continue to train the squat pattern in a tolerable fashion.

Last but not least, you can change bar position. Changing from a low bar squat to a high bar squat or vice versa, alters the torso angle, and thus the stresses on the hip. One may feel better than the other, so try them both and see what’s best for you.

Step 3: Remove the exercise and perform a different variation

We already touched a little on this in the prior step, but sometimes the painful exercise itself is so sensitized, that no matter what modifications you make, it still hurts. In this case, you may need to temporarily take a break from the squat, and perform an exercise that’s similar to it, but that doesn’t reproduce your pain.

Options include

- Split squat

- Rear elevated foot split squats

- Different lunge variations

Train one of the above exercises, pain-free, for a 4-6 week block and see how that goes. This will limit any kind of detraining, continue to promote a training stimulus, but allow enough time for the painful exercise to desensitize. Once the appropriate amount of time has passed, you can add the original exercise back into your training, which brings us to the next step.

Step 4: Reintegrate the initial lift and linearly progress.

This is the very step that many people mess up, which leads them down a path of never ending frustration. If you’ve taken time off from a lift and successfully reduced your pain, only to have it come right back as soon as you started doing it again, pay attention to this part.

The mistake many people make with reintegrating a once painful exercise back into their training program, is starting at too HIGH of an intensity, and too LOW of a frequency. What exactly does this mean?

It means that when you reintegrate a once painful exercise back into your regimen, you need to set both the actual AND relatively intensity very LOW and you need to perform that lift more than once a week!

Here’s an example. Let’s say you were squatting 315 lbs. for a painful set of 5. You’ve tried all of the recommendations above but came to the conclusion that the only solution was to temporarily remove the exercise and do reverse lunges for 4-6 weeks.

Now you’ve tested out the waters and you can perform a pain-free bodyweight squat, but what weight do you start back up at when you add the barbell? If your answer is anything above 135 lbs…it’s probably too much!!

In fact, if you’ve been dealing with the pain for an extended amount of time, I might recommend you start with just the 45 lb. barbell! While the actual starting weight upon returning to the lift is highly variable based on individual circumstances, I can tell you that most people start with too much weight.

Why a linear progression?

The entire goal of this process is to SLOWLY build back up your tolerance to the lift and bombard your system with a healthy stimulus. It may take MONTHS to return to your baseline, but so what? This is a marathon, not a race. If you want to truly overcome this issue once and for all, slow and steady is the way to go.

Because you’ll be starting significantly under your work capacity, you should now perform the lift 2-3x/week as well, slowly adding weight to the bar in a linear fashion every time.

For situations like these, I usually recommend sets of 5. Lower rep schemes usually don’t provide a significant stimulus, and higher rep schemes can induce too much fatigue. Neither of which is recommended for something like this!

The one trick up my sleeve…

If you’ve noticed, there are no mobility drills, soft tissue work, activation exercises, or manual therapy mentioned. Why? Because they aren’t necessary to overcome this issue. With that being said, the ONE thing I often do recommend if you have hip pain during squats is contracting and loading the hip flexor on the affected side.

Many times with this issue, you’ll find a weak hip flexor on the affected hip. While the weak hip flexor probably didn’t CAUSE the pain, it’s more likely a result of it. Things just don’t contract well when they hurt.

Sometimes hip pain during squats may even contribute to a case of hip flexor tendinopathy. Regardless, it can’t hurt to contract and strengthen that hip flexor, and it’s often beneficial for those who’ve been stretching the heck out of it for so long.

To do this, I like to use the heels elevated hip flexor march. I recommend performing them nice and slow and really focusing on the contraction at the top. You will be surprised at how quickly your affected hip fatigues!

You can dose these at 2-3 sets of 10 for 3x/week until your pain subsides, then reduce the frequency to just 10 reps during your warm-up.

If you need help with programming after an injury like this, I’d be more than happy to personally help you via our remote coaching option. For more information on that, check the link here. It’s time to finally get over this nagging issue of hip pain during squats!

(1) Frank JM, Harris JD, Erickson BJ, et al. Prevalence of Femoroacetabular Impingement Imaging Findings in Asymptomatic Volunteers: A Systematic Review. Arthroscopy. 2015;31(6):1199-204.