The squat is one of the most commonly trained exercises in both performance-based and rehabilitation-based training due to its status as a “weight-bearing, compound exercise that trains multiple muscle groups” (1). When teaching the squat to your clients, it is likely that they will eventually ask you if they should wear heeled weightlifting shoes.

Weightlifting shoes are one piece of equipment that recreational and competitive lifters often wear during squats as well as the Olympic weightlifting lifts (clean & jerk, snatch). In the following sections of this article, we will explore what weightlifting shoes are, what the available research reveals about their effects, and our recommendation for their use.

Weightlifting Shoe Information

The International Weightlifting Federation (IWF) provides a thorough historical perspective of the weightlifting shoe on their website and states that: “Weightlifting shoes are designed to allow the lifter to achieve a deeper squat, raise the heel on the rear foot in the split jerk and improve balance.” (2) The most important aspect of the weightlifting shoe, in terms of squatting, is likely the elevated heel.

According to the IWF, the elevated heel was added to the weightlifting shoe in the 40’s and 50’s after the squat became the preferred position for catching the clean and snatch, rather than the “deep-split” style used previously. The elevated heel was found to allow the lifter to catch the barbell at a lower position in a deeper squat and with improved balance.

Weightlifting Shoe Components Include:

- Heel Wedge: Typically .75”

- Firm Outsole/Midsole: Non-compressible TPU plastic, wood, or leather

- Stiff Upper: Provides stability, except for allowance of toe extension (split jerk)

- Straps/Boa-System: Additional stability for the mid-foot

Many powerlifters and athletes who train the squat have also adopted the use of weightlifting shoes due to the common coaching narrative that:

‘Weightlifting shoes (WS) allow the lifter to squat to a given depth, with a more upright trunk, due to decreased demand for ankle dorsiflexion affording increased knee flexion. The firm sole and lacing/strapping systems allow increased force production and stability for the lifter.’

The following section of this article will analyze the available research regarding this narrative.

Research Review

Multiple studies have looked at the effects of weightlifting shoes or elevation of the heels during the squat exercise. Interestingly enough, there is not much research looking at the effect of weightlifting shoes during the Olympic weightlifting lifts.

The bulk of research utilizes a high-bar back squat for assessment purposes, which sits in the middle of the knee/hip dominance spectrum of squat variants.

Range of Motion Considerations

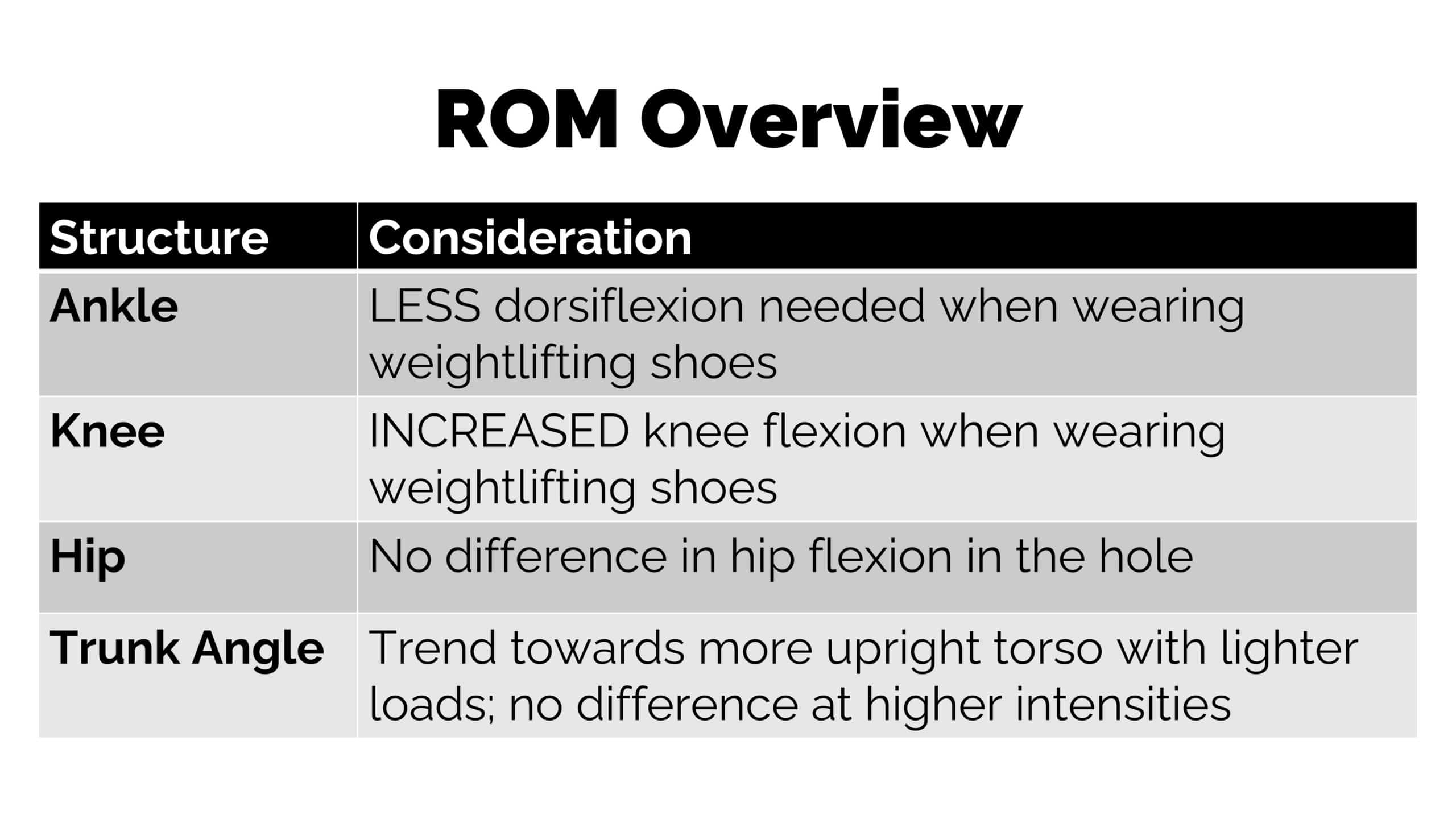

The potential effect of weightlifting shoes on lower body and spine range of motion is likely the most touted reason for the use of weightlifting shoes during the squat. Based upon the common narrative already discussed, a range of motion analysis of the ankles, knees, hips, and trunk is warranted.

Ankle

Weightlifting shoes' effect on ankle dorsiflexion was the most consistent across studies. Sato et al., Whiting et al., and Legg et al. all found statistically significant decreases in ankle dorsiflexion utilizing weightlifting shoes compared to the control group. Across studies, the average difference between groups ranged from approximately 2-5 degrees. Furthermore, Legg et al. found this change to be present in both novice and experienced lifters.

Knee

The study by Legg et al. found that both novice and experienced lifters had statistically significant increased knee flexion during the squat when wearing weightlifting shoes. Lee et al. and Sayers et al. demonstrated a small trend toward increased knee flexion with weightlifting shoes, but the difference did not reach statistical significance and thus should be considered with caution.

Hip

Across all studies, the effect of weightlifting shoes on hip flexion was only measured by Whitting et al. In their study, they found no significant effect of shoe type upon hip flexion at terminal depth.

Trunk Angle

The effect of weightlifting shoes or elevated heels on trunk angle during the squat reveals the most conflict in the current available evidence.

Sato et al. first demonstrated that weightlifting shoes decreased forward trunk lean during the barbell back squat performed at 60% 1RM, compared to running shoes.

Lee et al. and Whitting et al. later argued that Sato’s significant findings were due to the use of 2D analysis rather than 3D analysis in their study, and that trunk angle difference between groups was likely insignificant.

Legg et al. confirmed Sato’s finding during unloaded squats but found no difference in the loaded condition. Given that we are primarily concerned with loaded squats in this article, we would argue that Legg’s overall findings do not align with Sato’s.

Lee et al., Sayers et al., and Whitting et al. additionally found no difference in trunk angle between groups. Sayers et al. did find increased forward trunk lean in novice lifters compared to “regular” (experienced) lifters, but within each group weightlifting shoes had no significant effect compared to control.

If we are primarily concerned with loaded squats, then the only study which found a significant difference in trunk angle, between groups, was Sato et al.

With consideration of the critiques of Lee et al. and Whitting et al. on Sato’s 2D analysis, it is reasonable to conclude that the current totality of evidence does not show an effect of weightlifting shoes promoting a more upright torso during the barbell high-bar back squat.

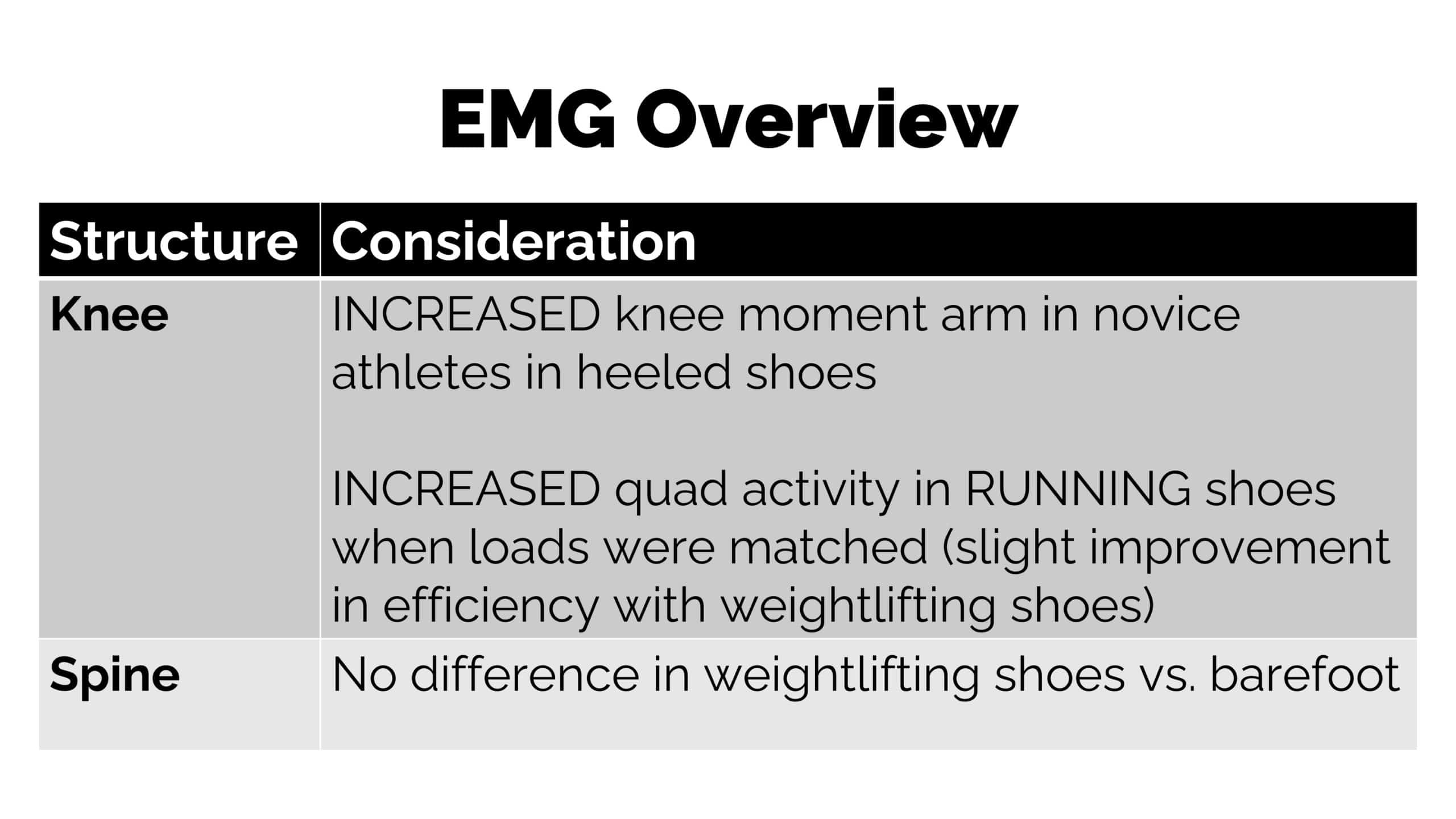

Moment/EMG

There is a smaller body of evidence looking at muscle excitation (EMG) differences between weightlifting shoes and a control group, compared to the investigation of range of motion differences.

Knee/Quadriceps

In regard to forces produced about the knee (moment), Legg et al. found increased knee moment in loaded squats performed by novice lifters in weightlifting shoes versus athletic shoes. This difference was not observed in experienced lifters.

The study by Beckham et al. found increased muscle excitation in the vastus medialis oblique (VMO), vastus lateralis (VL), and biceps femoris (BF) when barbell back squats were performed in running shoes, compared to weightlifting shoes, when loads were matched.

It is important to note that this difference between groups did not reach statistical significance, but an argument could be made that the trend of lower EMG for a load-matched performance indicates a slight improvement in lift efficiency with weightlifting shoes versus running shoes. Lee et al. also found no significant difference in vastus lateralis muscle excitation between groups.

Spine/Paraspinal

Looking at the effect of footwear on the low back, Sayers et al. found an increased L4/5 moment during the last 20% of the squat cycle in novice lifters on a level floor with regular shoes, compared to trained lifters. When heels were elevated to replicate the effects of weightlifting shoes, there was no difference found in L4/5 moment between experience levels.

Lee et al. found no significant difference in the EMG of thoracolumbar paraspinal or lumbar paraspinal musculature in a group of lifters wearing weightlifting shoes versus a level-floor barefoot condition.

Center of Pressure and Balance

Center of pressure measures have been investigated to determine if weightlifting shoes objectively demonstrate improved balance or stability over a control group.

Legg et al. found that in novice lifters, there was a significant reduction in ‘center of pressure variability (VCOP) in the medial/lateral direction and a non-significant reduction in the anterior/posterior direction. In experienced lifters, no difference was found in the medial/lateral direction but a significant difference was found in the anterior/posterior direction. This could be narrated as a decreased need for balance regulation when utilizing weightlifting shoes, which could be framed as more efficient.

Conversely, Whiting et al. found a statistically significant increased anterior/posterior peak center of pressure displacement in the group wearing weightlifting shoes, compared to running shoes. There was no difference in the medial/lateral direction. This did not agree with the authors’ hypothesis that weightlifting shoes would have a decreased peak center of pressure displacement.

In the only study found comparing the effect of weightlifting shoes on the snatch and clean, which consisted of one national-level weightlifter, there was an increased proportion of load on the forefoot when standard training shoes were worn instead of weightlifting shoes.

Perception of Stability

Whitting et al. utilized a visual analog scale in order to assess the perceived comfort and stability of both the weightlifting shoes and running shoes during the barbell back squat. They found that participants rated the running shoes as significantly more comfortable, but the weightlifting shoes as significantly more stable.

The authors put forth that these findings add nuance to the aforementioned findings that there was increased anterior/posterior center of pressure displacement in the weightlifting shoe group. They postulated that reduced amplitude of peak COP displacement “is not necessarily an indicator of greater balance, stability, or control.”

They further stated: “It may be that participants, who perceived the WS (weightlifting shoes) condition as more stable, were more confident and therefore allowed themselves to translate more in the A-P direction to manipulate the location of the load in relation to the base of support.”

Schermoly et al. also found a statistically significant improvement in perceived stability during the squat, when lifters used weightlifting shoes versus cross-training shoes.

Force Production

Schermoly et al. provide the only study looking at force transmission through the foot when using weightlifting shoes. Four groups were utilized: low-end powerlifting shoes, high-end powerlifting shoes, cross-training shoes with weight plates under the heels, and cross-training shoes alone. They found no differences in forefoot or rearfoot force production during the squat.

Research Synthesis

Analysis of the available research revealed heterogeneity of both methodology and results. Efforts were made to ensure certain principles were inherent to all papers utilized. All studies included, except Needham et al., utilized a barbell back squat, with most citing the use of “high-bar” placement. Additionally, all studies utilized some version of a loaded squat, except one group in the Legg et al. study, which was noted when referenced. Another aspect of heterogeneity between studies was the depth of squat, but no partial or half-squats were used in any study and all studies squatted roughly to “thighs parallel.”

The biggest potential limitation when applying the evidence discussed in this article lies in regard to the fact that no studies except for Needham et al. (n=1) assessed the front-rack squat/clean or overhead squat/snatch. This would be helpful information from researchers moving forward, relating back to the knee → hip dominance spectrum mentioned earlier.

Weightlifting shoes should theoretically assist the lifter more, as the lift becomes increasingly knee dominant (and therefore dorsiflexion-demanding) in the front-rack squat or overhead squat. Since modification of dorsiflexion-demand has been demonstrated through the use of weightlifting shoes, it makes sense to study their effect under conditions where there is a high demand for ankle dorsiflexion.

These conditions may reveal differences in range of motion, moment, EMG, etc., that differ from those shown in the high-bar back squat, adding value for coaches and lifters that utilize front-rack squats/cleans and overhead squats/snatches.

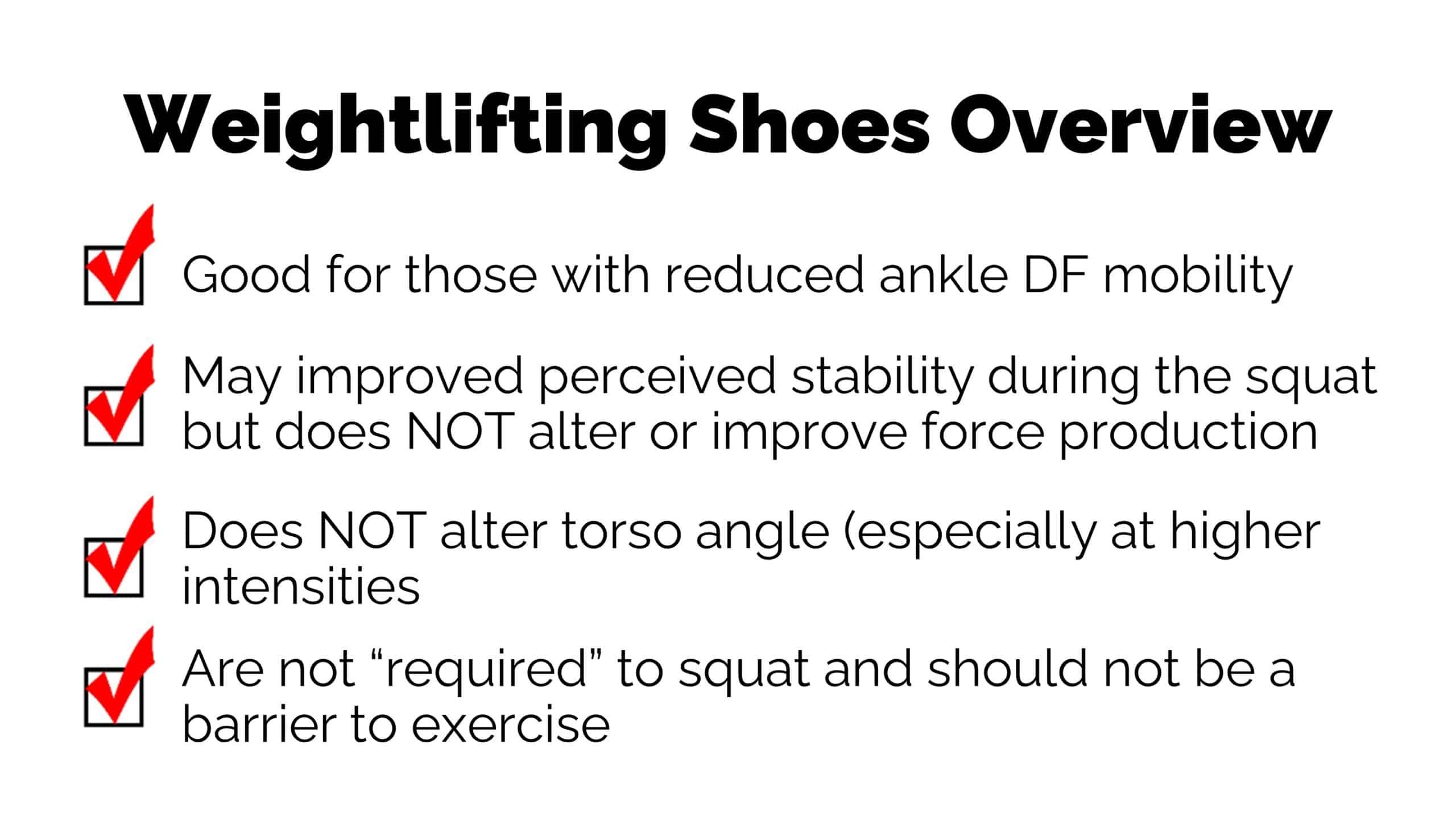

Putting it All Together

From the evidence discussed in this paper, an updated coaching narrative for the use of weightlifting shoes during the squat is:

‘Weightlifting shoes allow the lifter to squat to a given depth, with decreased demand for ankle dorsiflexion. Increased knee flexion, as a result, is weakly supported by evidence, but a more upright trunk is not supported. Weightlifting shoes have been demonstrated to improve the perception of stability during the squat, but do not demonstrate improved force production.

Simpler Terms: Weightlifting shoes may help improve the lifter’s comfort during the squat, especially in the presence of reduced ankle range of motion; and will likely improve their perceived stability.

Practical Recommendations

At Barbell Rehab, we firmly believe that barriers to activity and exercise should not be created unnecessarily; because a large number of barriers to physical activity already exist. As such, we strongly recommend that your clients perform a squat variation that aligns with their goals, abilities, and preferences; in a shoe that they currently own, especially in the presence of finite resources.

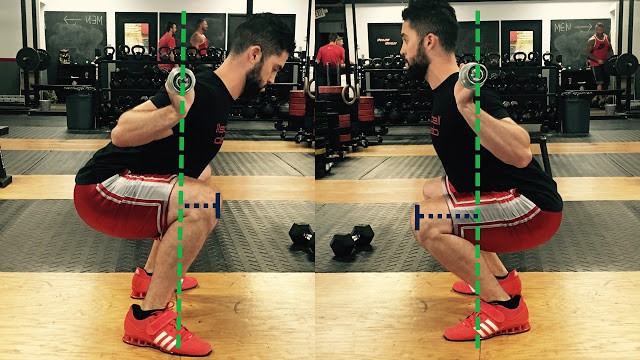

If ankle range of motion impacts your client’s ability to descend to a comfortable squat depth, we recommend elevating their heels on two weight plates to determine if it improves the trainability of the squat. If this is the case, then they may benefit from the use of weightlifting shoes or continuing to elevate their heels on weight plates, especially in the short-term.

It is likely that with time and practice, similar to other skills, your client’s ability to squat efficiently will improve regardless of the utilization of weightlifting shoes.

In terms of your client who...

- Wants to compete in a powerlifting meet, or compete in Olympic weightlifting

- Demonstrates improvement with an elevated-heel squat, demonstrates interest, and has the resources to purchase weightlifting shoes

- Demonstrates an efficient squat without an elevated-heel but is interested in utilizing a weightlifting shoe for other potential performance improvements described in this article

… then we would recommend having a conversation with them regarding the potential benefits of adding a pair of weightlifting shoes to their gym bag.

References

- Lee, Szu-Ping, et al. “Heel-Raised Foot Posture Does Not Affect Trunk and Lower Extremity Biomechanics During a Barbell Back Squat in Recreational Weight Lifters.” Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, vol. 33, no. 3, 2019, pp. 606–614.

- Whitting, John W, et al. “Influence of Footwear Type on Barbell Back Squat Using 50, 70, and 90% of One Repetition Maximum: A Biomechanical Analysis.” Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, vol. 30, no. 4, 2016, pp. 1085–1092.⠀

- Sayers, Mark G. L, et al. “The Effect of Elevating the Heels on Spinal Kinematics and Kinetics during the Back Squat in Trained and Novice Weight Trainers.” Journal of Sports Sciences, vol. 38, no. 9, 2020, pp. 1000–1008.⠀

- Needham, Robert, et al. “Does the Sport of Weightlifting Need Special Shoes?” Footwear Science, vol. 11, no. sup1, 2019, pp. S155–S156.⠀

- Legg, Hayley S, et al. “The Effect of Weightlifting Shoes on the Kinetics and Kinematics of the Back Squat.” Journal of Sports Sciences, vol. 35, no. 5, 2016, pp. 508–515.

- Beckham, George K, et al. “EMG Activity Of Leg Musculature During The Back Squat With Weightlifting And Running Shoes.” Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise, vol. 46, 2014, p. 822

- Sato, Kimitake, et al. “Kinematic Changes Using Weightlifting Shoes on Barbell Back Squat.” Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, vol. 26, no. 1, 2012, pp. 28–33

- Schermoly, Thomas P, et al. “The Effects of Footwear on Force Production During Barbell Back Squats.” Journal of Undergraduate Kinesiology Research, vol. 10, no. 2, 2015, pp. 42-51.