The barbell bench press has often been described as the “king” of upper body strength assessments. It is utilized to assess strength in powerlifting competitions via a 1-repetition maximum (1RM) and muscular strength/endurance in the NFL combine. To this day, it remains one of the first upper body exercises taught to novice lifters internationally.

Bench Press Overview

The barbell bench press can be utilized to build the endurance, strength, and power of both horizontal and vertical pressing movements. Sport-specific movements that may benefit from a strong/powerful bench press include blocking in football/rugby and checking in hockey/lacrosse.

The bench press also serves as an excellent exercise for those with chiefly aesthetic and hypertrophy goals. Furthermore, training the bench press undoubtedly serves a role in the injury-risk reduction seen with strength and conditioning programs, due to the effects of increased bone-mineral density, muscular performance, tendon stiffness, and joint conditioning.

Bench Press Target Muscles and Variations

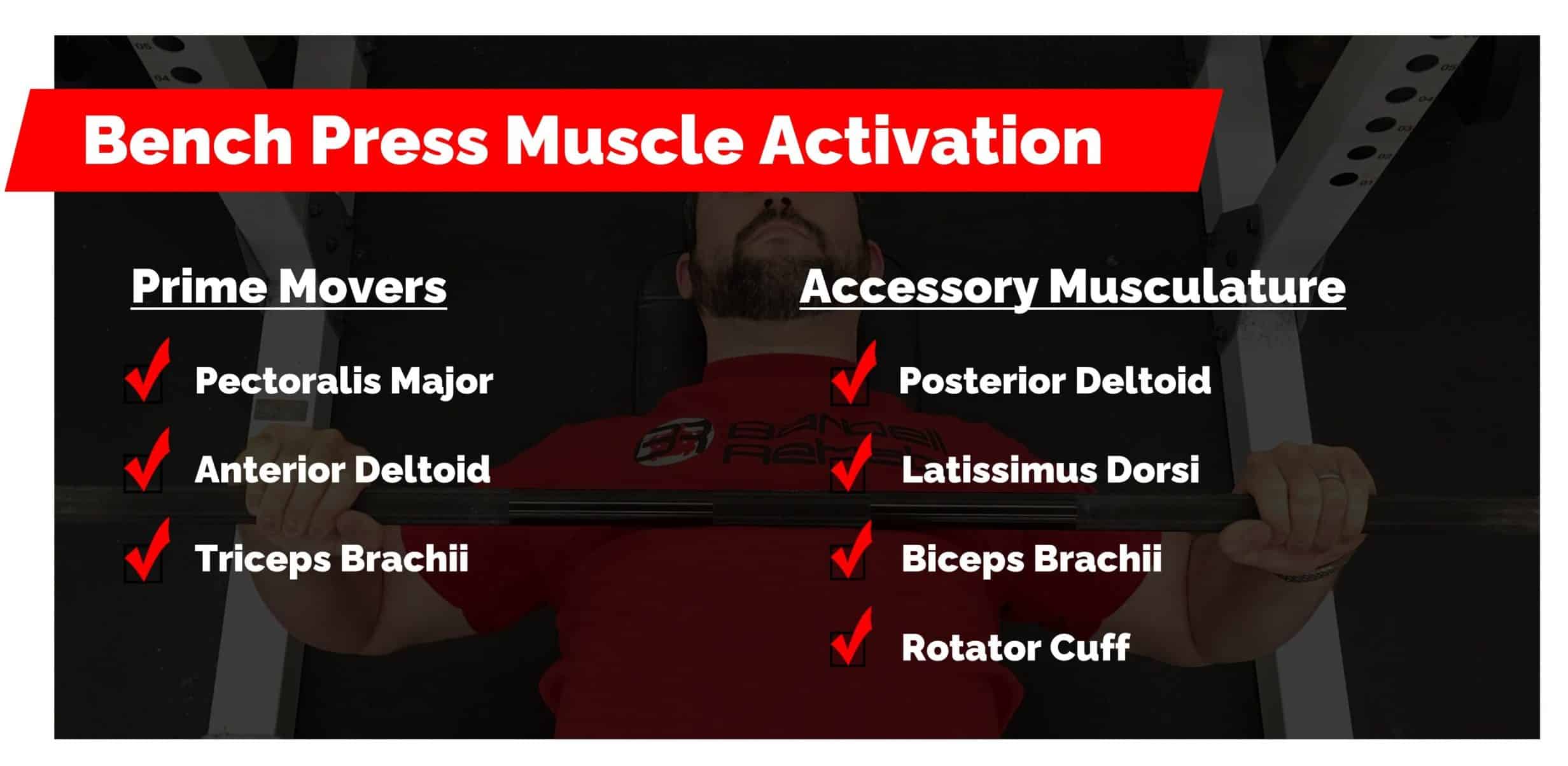

Agonist muscle groups involved with the bench press include pectoralis major (clavicular and sternal heads), anterior deltoid, and triceps brachii musculature. EMG studies have also demonstrated muscle excitation of posterior deltoid, latissimus dorsi, biceps brachii, and rotator cuff musculature.

There are many variations of the barbell bench press, although a barbell bench press performed on a flat bench is likely the most commonly utilized. Variations include the use of an incline or decline bench; the use of a narrow, medium, or wide-grip; and the use of a reverse-grip (double-supinated) rather than a standard grip (double-pronated/overhand).

Why is this important? Knowing the differences between these variations can help drive the decision making process for which one to use in different performance and rehab-based scenarios.

Classic Narratives Regarding the Bench Press

When it comes to the barbell bench press, there are some common narratives you might hear, including:

- “Incline bench press works your upper chest more”

- “Decline bench press works your lower chest more”

- “Narrow grip bench press works your triceps and anterior deltoids more”

- “Wide grip bench press works your pectoralis major more”

- “Reverse grip bench press works your upper chest more”

While some of these may have some truth and merit, let’s dig into the details.

Effect of Bench Angle on Range of Motion

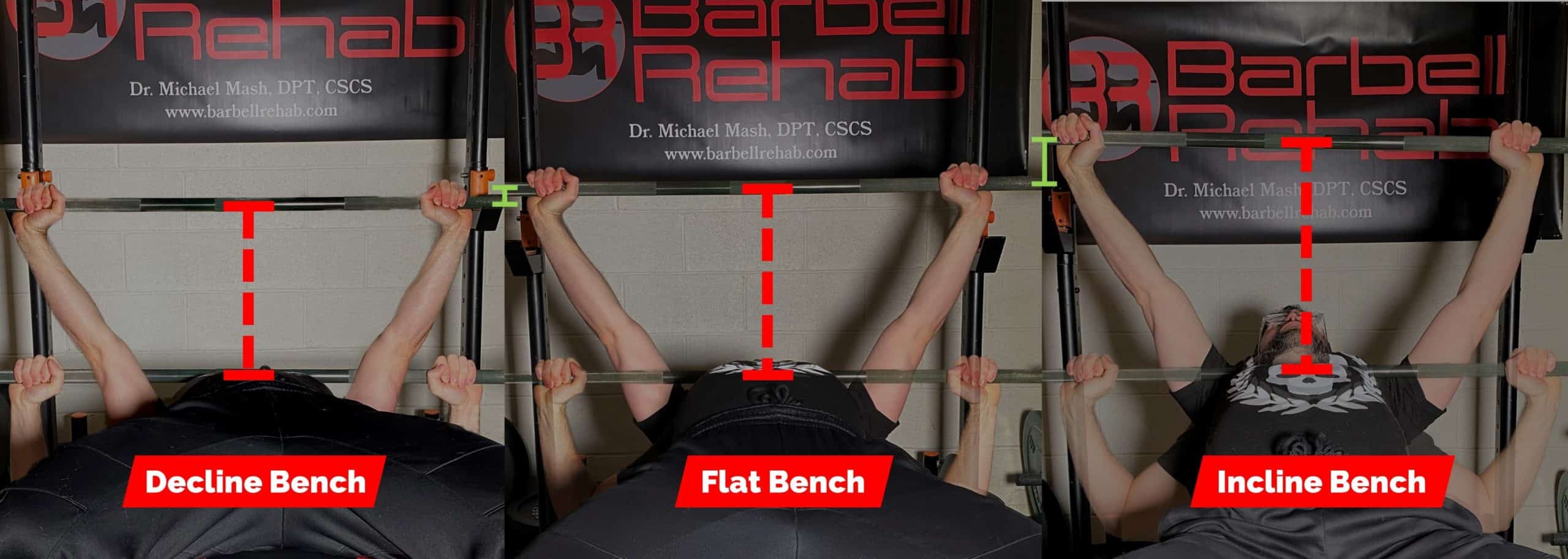

While no studies assessing shoulder range of motion during the barbell bench press were found, Saeterbakken et al. assessed barbell vertical displacement and elbow flexion range of motion under 5 different bench press conditions. It is important to note that this study was performed on twelve experienced athletes who competed in the bench press at the national or international level.

For reference, the vertical displacement is the overall vertical distance the bar travels during one rep. When looking at this, the authors found that barbell vertical displacement increased with incline bench press compared to decline bench press (shown in the picture below). They also found that elbow flexion at the lowest bar position increased with incline bench press compared to decline bench press.

Note the increased vertical displacement with the incline bench

In both of these situations, there was no significant difference when comparing either incline/decline bench press to flat bench press but the vertical displacement and elbow flexion range of motion fell, predictably, in between the other two for flat bench press.

Effect of Grip Width on Range of Motion

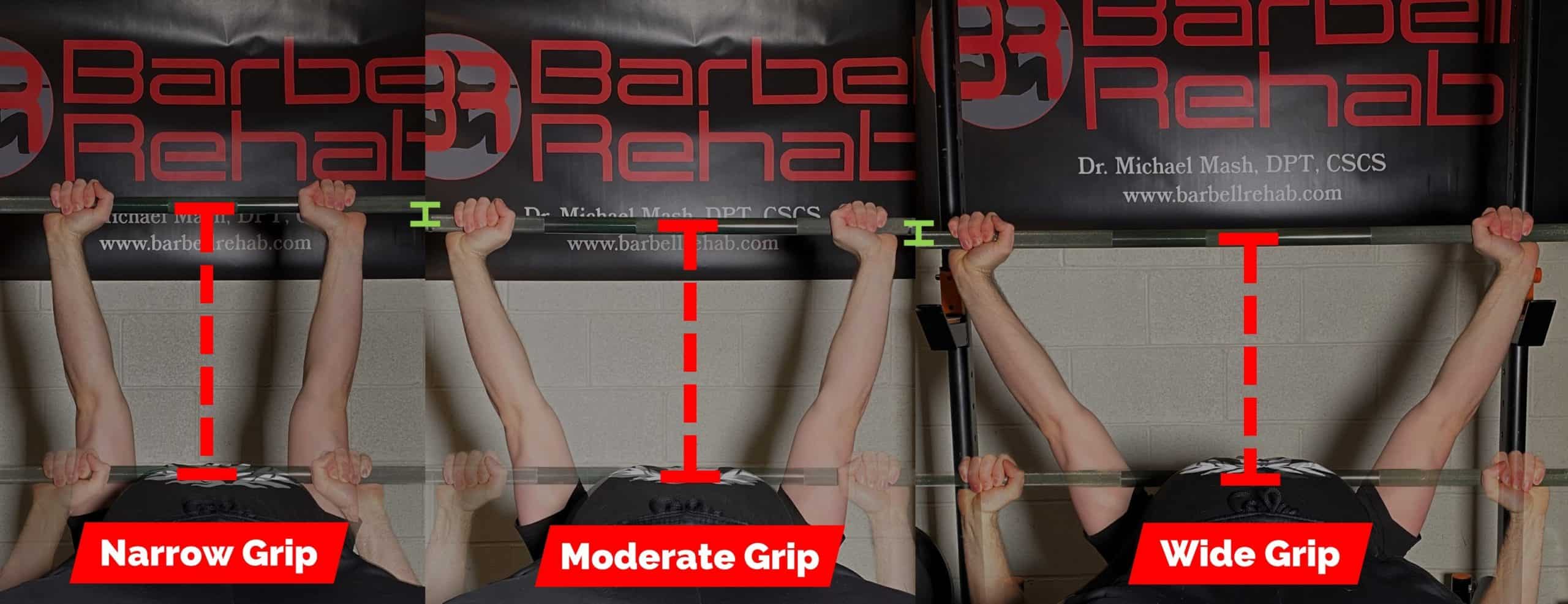

Saeterbakken et al. also demonstrated that barbell vertical displacement increased with a narrow and medium grip compared to a wide grip bench press (shown in picture below). There was no significant difference in barbell vertical displacement between the narrow and medium group, although the trend was increasing displacement with decreasing grip width.

Furthermore, they found that elbow flexion at the lowest bar position increased with a narrow grip compared to a wide grip. In this situation, the medium grip width elbow flexion fell in between the wide and narrow but with statistically significant difference from either.

Note the increased vertical bar displacement present with narrow grip

While not assessed, it can be postulated that the trend for increased elbow flexion also led to increased shoulder extension/horizontal abduction. As such, the narrow grip and incline bench press groups are likely to have increased shoulder extension/horizontal abduction compared to the wide grip and decline bench press groups, respectively.

Effect of Bench Angle on Muscle Excitation

In the same Saeterbakken et al. study as cited above, the authors set the incline, flat, and decline bench set-up at +25°, 0°, and -25°, respectively, and had each athlete perform a 6RM bench press on each.

A wide-grip was utilized with each position. During testing, surface EMG was recorded for both clavicular and sternocostal heads of the pectoralis major, triceps brachii, biceps brachii, anterior deltoid, posterior deltoid, and latissimus dorsi.

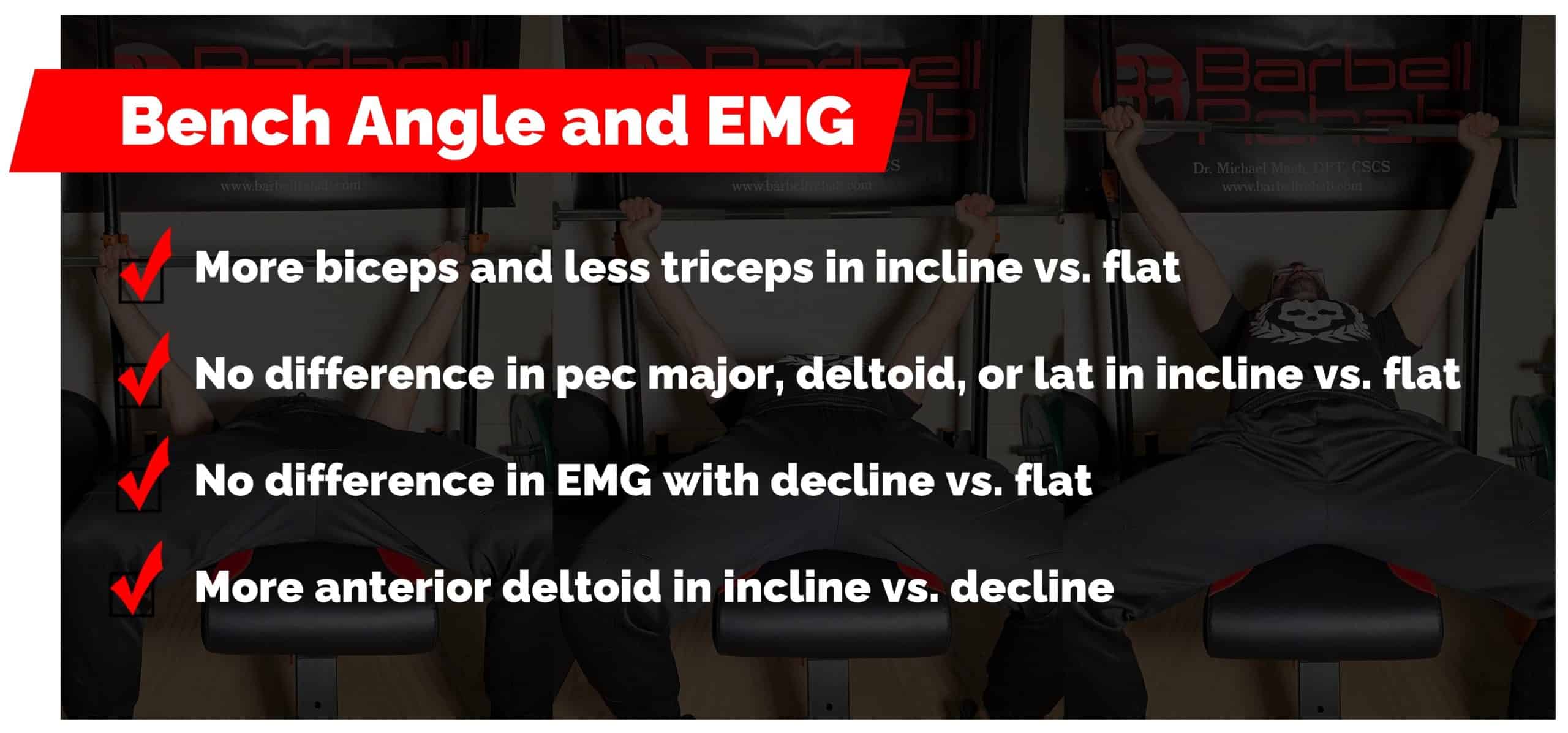

Comparing incline bench press EMG to flat bench press EMG, there was a 58.5% decrease in tricep brachii muscle excitation and a 48.3% increase in biceps brachii muscle excitation in the incline bench press set up. Pectoralis major (both heads), anterior deltoid, posterior deltoid, and latissimus dorsi muscle excitation was similar between incline and flat bench press.

Comparing decline bench press EMG to flat bench press EMG, there were no significant changes in muscle excitation in any of the muscle groups studied. Bench angle and EMG findings can be summarized in the graphic below:

To clarify further, decline bench press did demonstrate statistically significant EMG differences in tricep and bicep excitation when compared to incline bench press, but these differences were not significant compared to flat bench. In other words, most of the EMG changes occurred from lowering the bench angle from +25° to 0°.

There was a statistically significant 25.7% increase in anterior deltoid excitation in the incline bench press position compared to the decline bench press, but no significant difference when comparing incline or decline to the flat bench.

In summation, the incline bench press led to statistically significant increased biceps brachii excitation and decreased tricep brachii excitation when compared to both flat and decline bench press. Statistically significant increased anterior deltoid excitation was shown when comparing incline to decline bench press, but not incline to flat bench press.

Effect of Grip on Muscle Excitation in Elite Lifters

Saeterbakken et al. also examined the effect of wide, medium, and narrow grip width on muscle excitation during the flat bench press. A 6RM bench press was, again, utilized for each condition.

The wide grip set-up was 81cm between the hands, which is consistent with the max width allowed in many powerlifting federations. The narrow grip width was set at the athlete’s biacromial distance, or roughly an “armpit to armpit” distance. The medium grip width was set at halfway between the wide and narrow grip. The same muscles assessed via EMG in the incline/flat/decline conditions were assessed here.

The only significant difference in EMG findings between the narrow, medium, and wide grip bench press was related to the biceps brachii. The biceps brachii excitation in the narrow grip bench press was decreased 30.5% and 25.9% compared to the medium grip and wide grip bench press, respectively. It’s important to keep in mind here though that this study was performed on subjects who competed professionally in the bench press. So, the question remains, would we see a difference in more novice trainees?

Grip Width and Muscle Activity in Recreational Lifters

Lehman also examined the effects of wide, medium, and narrow grip width on muscle excitation during the flat bench press, utilizing both pronated (overhand) and supinated (reverse) grips.

Of note, the supinated condition was only tested at medium and wide grip widths. Wide grip in this study was considered 200% of biacromial distance, medium grip was considered 100% of biacromial distance (“narrow” grip in the Saeterbakken at al. study), and narrow grip was considered a grip with just one hand’s width between each hand.

Methodologically, the author assessed EMG during a 5 second isometric pause with the barbell held 1 inch above the athlete’s chest. The 12RM load for the supinated medium grip bench press was utilized across all trials. This was performed in a sample of 12 male college students with greater than 6 months of weight training experience.

The author found that the pectoralis major’s clavicular head demonstrated increased excitation during a supinated grip compared to the pronated grips. Pectoralis major’s sternal head demonstrated increased excitation with the wide grip width compared to the narrow grip width, but was not affected by supination. Muscle excitation of the triceps brachii was greatest with a narrow/pronated grip. Triceps excitation decreased with increasing grip width during both pronated and supinated conditions.

Lehman’s data on biceps brachii excitation showed no significant difference between the three pronated grip widths. This disagrees with the work of Saeterbakken et al. that demonstrated significantly decreased biceps brachii excitation in the equivalent of Lehman’s medium grip compared to each studies similar wide grip. Potential contributing factors to the different findings include population (competitive vs. recreational), contraction type (isotonic vs. isometric), and intensity (6RM vs. 12RM).

Lehman’s data did show a significant difference of increased biceps brachii excitation in the supinated group compared to the pronated group with a matched grip width. Additionally, the supinated wide grip width bench press demonstrated significantly increased biceps excitation compared to the supinated medium grip width.

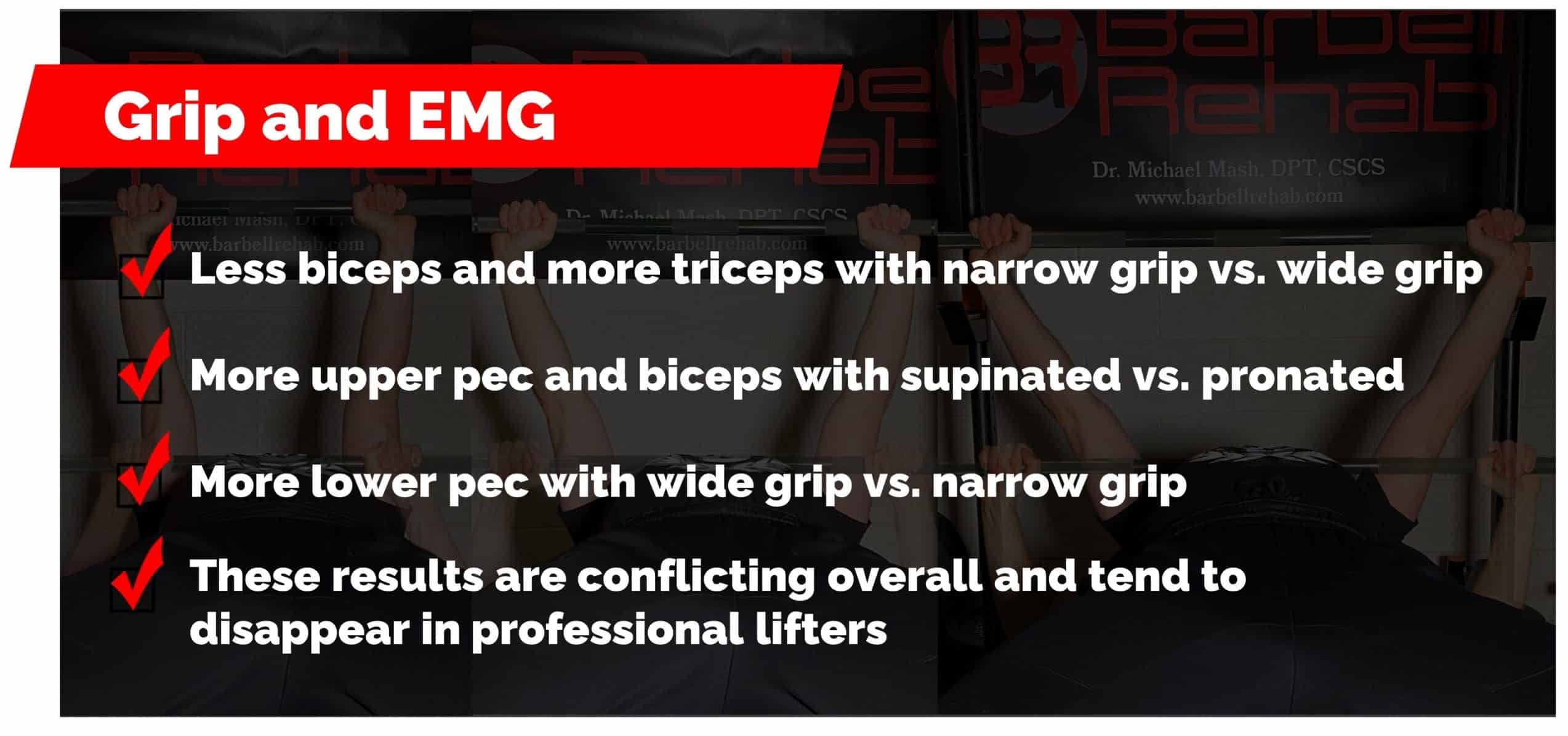

We’ve combined the results of both of the aforementioned studies on grip and EMG into graphic below:

In summation of grip width’s effect on EMG, the two available studies demonstrated conflicting results regarding:

- Decreased biceps brachii excitation during the bench press at shoulder width (100% BAD) compared to wide grip (significance demonstrated by Saeterbakken et al.)

- Increased tricep brachii excitation during the bench press at shoulder width (100% BAD) compared to wide grip (significance demonstrated by Lehman)

In summation of reverse grip bench press vs. standard grip bench press, Lehman found:

- Increased biceps brachii excitation during reverse grip bench press, with further increased excitation with a wider reverse grip compared to a shoulder width reverse grip width.

- Increased clavicular head of pectoralis major excitation with reverse grip bench press

Effect of Bench Angle and Grip Width on External Load

In the study by Saeterbakken et al, which consisted of competitive bench pressing athletes, the effects of bench angle and grip on 6RM load were assessed.

6RM load was 21.5% higher in the flat bench compared to incline bench press. 6RM load was 2.5% higher in the flat bench press compared to the decline bench press, which did not reach statistical significance.

6RM load was highest in the wide grip bench press condition, demonstrating 5.8% higher loads than the medium grip bench press and 11.1% higher loads than the narrow grip bench press. Both of these reached significance, as did the difference between medium and narrow grip bench press.

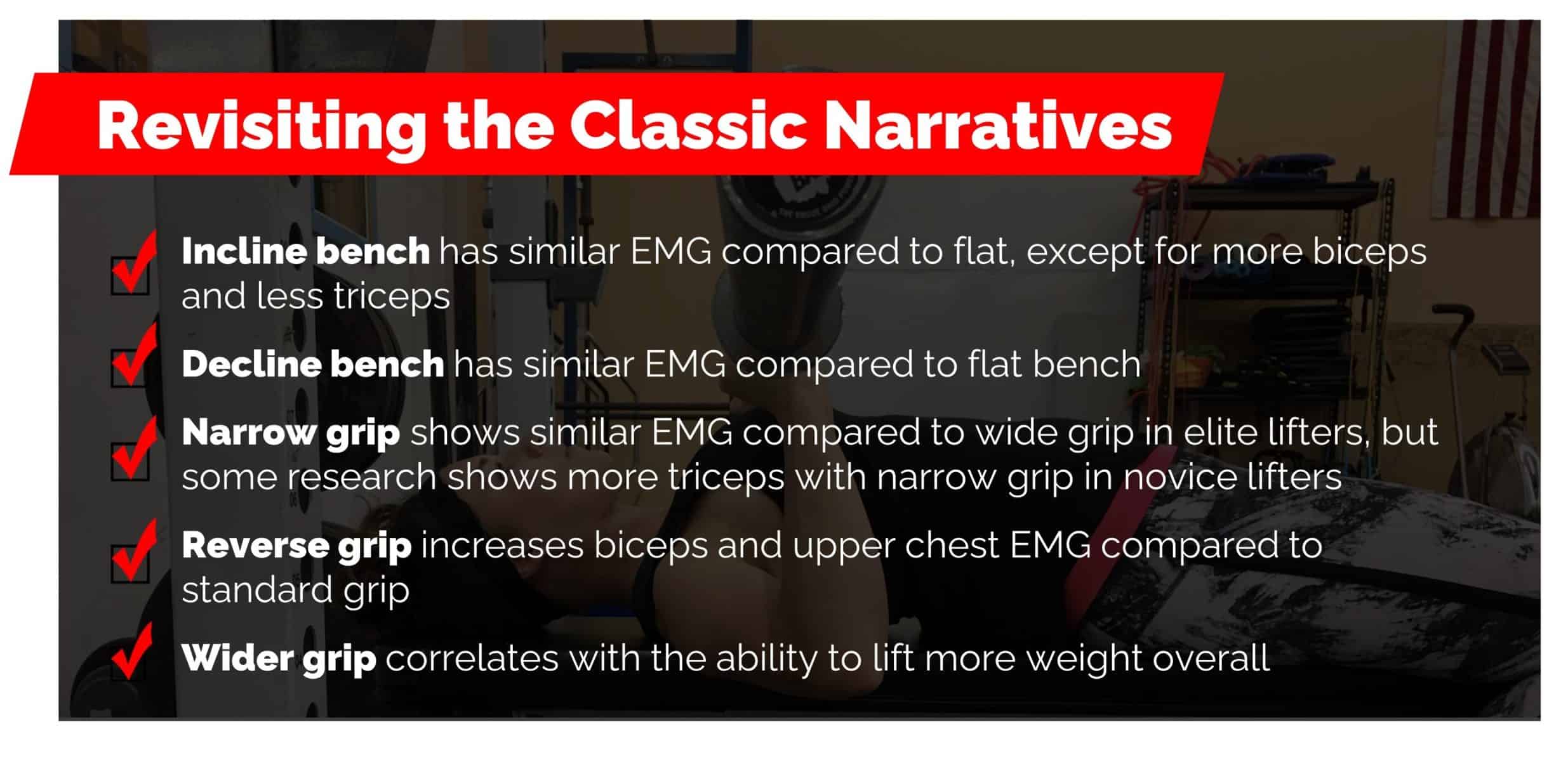

Revisiting the Classic Narratives Regarding Bench Press

Compiling all of the information above, let’s revisit our classical narratives regarding bench press grip width and angle and see what we get.

As you can see, due to conflicting results reported by some studies, it can be difficult to give clear cut answers, but trends are definitely present.

Rehab Considerations for the Bench Press

One of the main goals of this article was to assess, within the available literature, some of the differences between the barbell wide grip flat bench press, often referred to as “competition style,” and the variations of this exercise. With some of these differences brought to light, there are potential benefits of using this information with your clients who are working through pain in the bench press.

While this article will not provide an overview of constraint-based training (i.e. ROM modification, tempo modification, internal/external load modification) for the bench press in the presence of pain, there is still some utility in the above information. To read our article on how to modify the bench press when pain is present, just head right here.

Example 1: Elbow Pain During the Bench Press

Your client is having left elbow pain at the lowest bar position of a medium grip incline bench press on any given day/week of training. One option in this situation would be to switch to a wide grip decline or flat bench press. Based upon the above information, this would decrease both elbow range of motion at the lowest bar position and the global range of motion in terms of vertical barbell displacement. If the external load was kept similar then this would also result in a decreased relative load compared to the variation specific 1RM.

Example 2: Bench Pressing After a Biceps Tear

Your client, in a physical therapy/rehabilitation setting, has just been given the go from his MD (and yourself) to return to a barbell training progression following a distal biceps tendon repair. Knowing the differences between the above variations, a flat bench press with a narrow grip, performed with depth to tolerance, may be a better choice initially than an incline bench press with a wide grip or a reverse grip bench press. This is due to the potential for increased biceps brachii excitation and increased global/elbow (and likely shoulder) range of motion requirements found with a narrow grip and incline bench press; and the increased biceps brachii excitation found in the reverse grip bench press.

A Note on EMG Studies

While EMG studies are useful for conceptualizing the process that the neuromuscular system undergoes during exercise, recent literature has questioned the validity of EMG for estimating, alone, the long-term effects on hypertrophy and strength that increased vs. decreased EMG may provide.

With the small changes between variations and the potentially imperfect validity of EMG in mind, Lehman concludes: “Considering the small changes that occur during changes in grip width, the choice of grip position should be determined by the positions athletes adopt during their sport. Sport specificity should supercede attempts to train specific muscle groups.”

For further reading on this topic, check out the Vigotsky et al. paper in the references below.

References

Saeterbakken, Atle Hole, et al. “The Effects of Bench Press Variations in Competitive Athletes on Muscle Activity and Performance.” Journal of Human Kinetics, vol. 57, no. 1, 2017, pp. 61–71.

Lehman, Gregory J. “The Influence of Grip Width and Forearm Pronation/Supination on Upper-Body Myoelectric Activity during the Flat Bench Press.” Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, vol. 19, no. 3, 2005, p. 587.

Wattanaprakornkul, Duangjai, et al. “Direction-Specific Recruitment of Rotator Cuff Muscles during Bench Press and Row.” Journal of Electromyography and Kinesiology, vol. 21, no. 6, 2011, pp. 1041–1049.

Vigotsky, Andrew D, et al. “Interpreting Signal Amplitudes in Surface Electromyography Studies in Sport and Rehabilitation Sciences.” Frontiers in Physiology, vol. 8, 2017, p. 985.