Persistent, or chronic pain has progressively increased in prevalence over the past decades, with recent studies reporting between 11-40% of US adults dealing with persistent symptoms (1). If you are one of those folks reading this right now, or you’re a professional who routinely works with clients with persistent pain, there’s a good chance the barbell lifts may be your go to mode of exercise and strength training. However, many folks with persistent pain are fearful of worsening their symptoms and damaging their bodies if they engage in strength training.

Fortunately, our scientific understanding of persistent pain has grown exponentially in recent years, demonstrating a multitude of benefits for both aerobic exercise and strength training (2, 3, 4). In this article, we will explore a few pivotal topics to help those with persistent pain get back to training and living a meaningful life aligned with their values.

Pain Neuroscience Education and Persistent Pain

Pain neuroscience education, or PNE, has received A LOT of attention over the past years since Explain Pain was first published in 2003 (22). However, recent studies have questioned the efficacy of using PNE as a stand-alone intervention to treat persistent pain (5). Nevertheless, PNE has consistently demonstrated changes in both fear avoidance and disability. In addition, PNE was never intended to be used as a stand-alone intervention and should always be used in a manner to decrease fear and help move folks in the direction of their goals.

Accordingly, fear avoidance is where I believe PNE has the greatest utility. Let’s use an analogy for example. Imagine you wake up in the middle of the night in a new luxurious, multi-room hotel suite needing to use the bathroom. It’s pitch-black thanks to the hotel’s premier drapery, and you’re uncertain of the exact path to pursue. You will most likely proceed on your quest with great caution and hyper-vigilance to ensure you avoid any self-sabotage such as kicking a dresser or tripping over an inconveniently placed ottoman. On the other hand, a simple flip of a light switch would illuminate a great many potential roadblocks, which would decrease the threat of the journey and greatly improve the efficiency of getting on with the task to return to sleep. I view the power of that handy light switch similarly to the benefits of PNE; understanding more about pain is just like flipping on the light switch to better illuminate the road to your destination!

By better understanding how pain works and its poor correlation to tissue damage, you will likely be much more comfortable engaging in movement and not worrying about the painful body part every time you feel increased pain. You can move with less caution and hyper-vigilance, which in turn, can help facilitate greater success in taking consistent action towards meaningful activities. Your pain may not necessarily change, but your willingness to experience discomfort likely will.

Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) and Persistent Pain

Speaking of willingness to experience discomfort, pain is a normal part of the human experience and serves an important role. However, once pain becomes persistent, and is no longer serving the role of accurately monitoring safety, it must be reframed to engage in life regardless of discomfort.

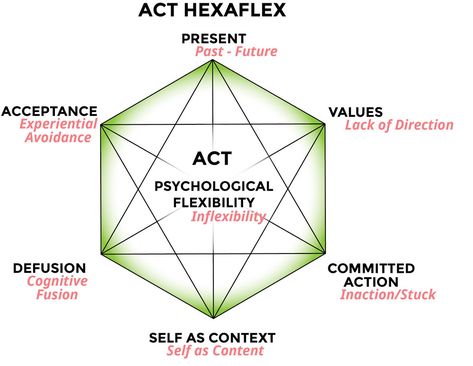

In addition to utilizing PNE, acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) is another powerful tool that has gained growing support in the scientific research recently to decrease suffering and disability (6). ACT uses acceptance and mindfulness strategies, together with commitment and behavior change strategies, to increase psychological flexibility. Taking it a step further, there are six main components of ACT: presence, acceptance, values, defusion, self as context, and committed action, which help guide the individual towards the concept of “psychological flexibility”.

Exploring the role of each component is outside the intent of this article, but we will briefly touch on a few: acceptance, defusion, values, and committed action. According to ACT research, when considering how to live a meaningful life, values are our North Star. Everyone’s values are unique to themselves, but once again, if you are reading this article, prioritizing health and fitness are likely involved on your list. This would suggest that acting on those values would be “worth suffering for.” However, this is not meant to be a masochistic oath. Instead, it’s being willing to experience pain (acceptance) and utilizing defusion (not identifying with self limiting thoughts that arise) to engage in meaningful activities aligned with your values by taking committed action (6).

If you’re worried I’m suggesting to exercise with pain if the value of health and fitness resonates with you, I’m sorry to inform you that you’re indeed, spot on. Fear not though! Some recent research tells us it is safe to exercise with pain and may even be advantageous (7)!

Pain with Exercise and Lifting Weights

A 2017 systematic review by Ben Smith and colleagues (7) concluded that “Protocols using painful exercises offer a small but significant benefit over pain-free exercises in the short term” and “Pain during therapeutic exercise for chronic musculoskeletal pain need not be a barrier to successful outcomes.” This review can lend further confidence to engaging in exercise with a tolerable level of pain, which is different for each person. Nevertheless, due to unique characteristics of various pain experiences, the most important factor when engaging in an exercise program is the dosage.

Dosage involves how much frequency, intensity, and volume is involved in a program and will be further discussed later. Depending on the unique conditioning and sensitivity levels of a person, dosage will have to be adjusted to facilitate optimal adaptations and consistency in participation.

Flexibly Persisting. Exercising with Pain

This all comes back to a concept from a 2018 study by Dr. Bronnie Thompson (8) exploring the similarities of folks who identify as “living well with pain”. It is a phenomenal article, which I would encourage everyone to read, but one of the main take-aways is the concept of flexibly persisting. The author describes flexibly persisting as

“The third phase of living well with chronic pain, which is an ongoing, lifelong process. It involves developing clarity about what is important in life, persisting with valued occupations, and being flexible when tackling challenges. Ongoing pain is accepted as a reality in life, but pain no longer holds the threat value it has while making sense. People in this phase are willing to experience fluctuations in pain when perceived rewards from these occupations are greater than the negative effects from increased pain or effort. Rather than managing pain, people in this phase begin to manage their lives, goals and actions.”

Due to the dynamic and emergent nature of pain, which is part of the complex human experience, symptoms will often vary day to day. Therefore, in order to stay consistent with taking committed actions towards values, it is often necessary to be willing to make adjustments to the route one takes to accomplish goals aligned with said values.

As you can probably see, this ties in very nicely with ACT and reinforces the need for willingness to experience setbacks and have wiggle room in plans. A great way to stay flexible with training is utilizing RPE or RIR to dictate training intensity for the day versus sticking with a strict program based on 1RM.

Flare Kits for Self Managing Pain

Even when all of the above topics are incorporated well into one’s life, pain will still inevitably get the best of folks some days. This brings us to our next topic: flare kits. A flare kit is a concept regarding a plan to utilize when pain does increase beyond tolerance. This can include a multitude of tools, such as heat, ice, a warm bath, a walk, breathing or mindfulness exercises or a number of any other strategies found useful that don’t create reliance, decrease self efficacy or possibly harm oneself long term (i.e. opioids or substance abuse).

These can be super helpful, but it’s important to remember what these tools are and are not doing. They can be great for short term modulation of pain perception but tools such as heat or ice are not actually changing any “pain producing inflammation” or “melting muscle knots”. Additionally, if you are having to consistently fall back on your flare kit, it is likely time to zoom out to consider your overall programming and lifestyle and make modifications of different variables as needed.

Exercise and Conditioned Pain Modulation

We have a growing amount of evidence to support the notion that conditioned pain modulation (CPM) is less effective in folks with chronic pain (9, 10, 11). CPM is a mechanism in which endogenous chemicals are released in the body to decrease pain as a result of increased nociception appraised as non-threatening within a certain context. In other words, “pain inhibits pain.” A prime example of this is when your older sibling may have punched you in the arm as a child to decrease your complaining about a different body part such as stubbing a toe.

An article by Polaski et al in 2019 (12) provides support for the use of exercise to improve the CPM system. Another article by Andrade et al in 2018 (13) exploring strength training with fibromyalgia concluded,

“Strength training (ST) had positive effects on physical and psychological symptoms, in terms of reducing pain, the number of tender points, and depression, and improving muscle strength, sleep quality, functional capacity, and quality of life. Intervention protocols should start at low intensity (40% of 1RM) and gradually increase the intensity. ST should be performed 2 or 3 times a week to exercise the main muscle groups. The current studies showed that ST is a safe and effective method of improving the major symptoms of FM (fibromyalgia) and can be used to treat patients with this condition.”

Although CPM can be leveraged via both strength and aerobic training, recent trials have tended to point more towards the aerobic option, which may be due to increased ease with achieving an elevated heart rate over a longer period of time (14, 15).

Regardless, appropriately dosed resistance training can likely help facilitate improved functioning of the conditioned pain modulation system.

Exercise Dosage for Persistent Pain

“All things are poisons, for there is nothing without poisonous qualities. It is only the dose which makes a thing poison.”― Paracelsus.

Exercise dosage for persistent pain can be one of the greatest challenges. Currently, we do not have any definitive metrics in the research evidence to this point. A recent systematic review looking at the optimal exercise dosage to leverage conditioned pain modulation by Polaski et al. in 2019 (12) concluded “Overall, this analysis of the existing literature demonstrated insufficient evidence for the presence of dose effects of exercise in relation to analgesia.”

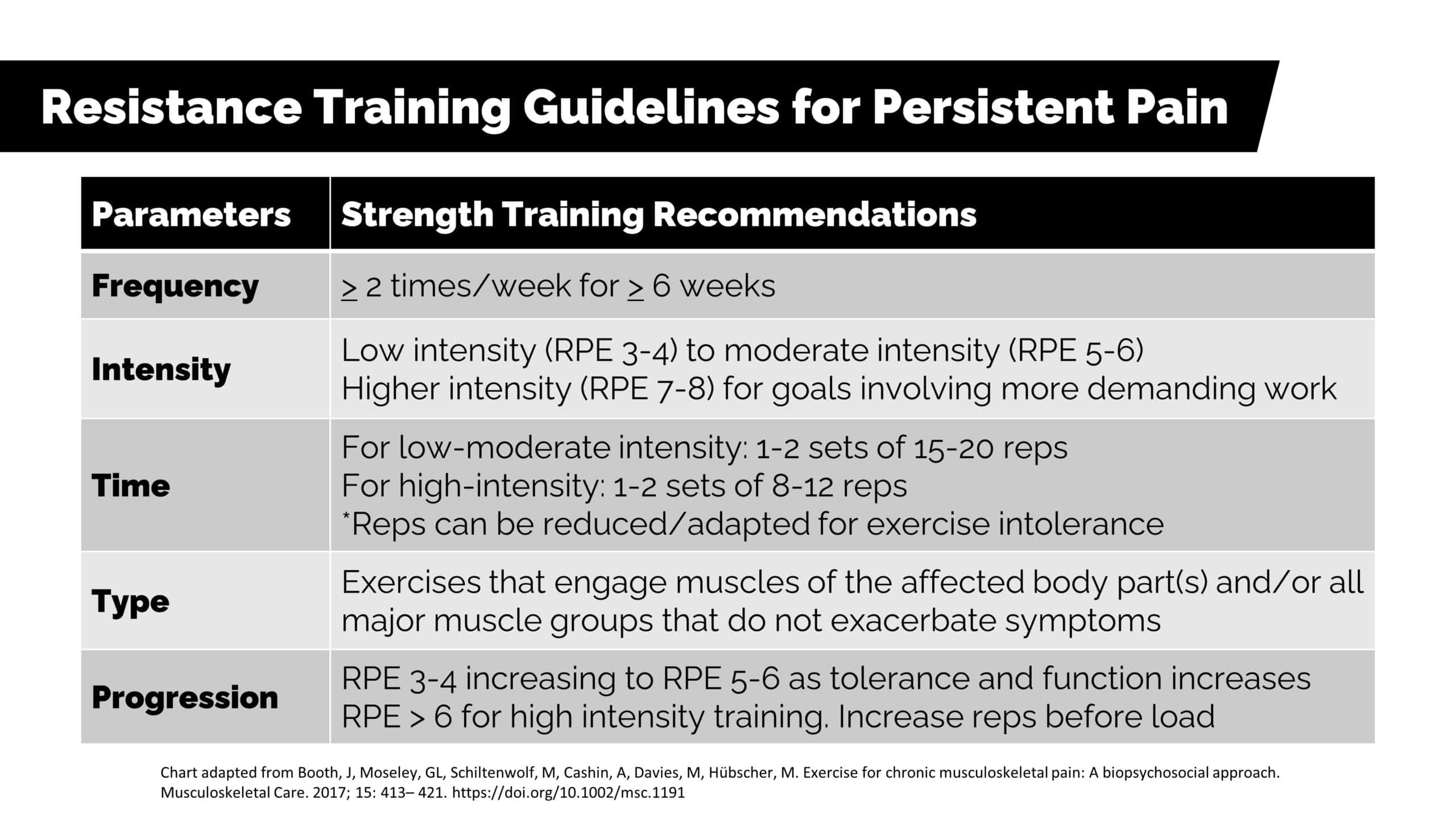

We have a plethora of evidence demonstrating efficacy with exercise for chronic pain, but the optimal dose remains uncertain. Additionally, dosage is extremely difficult to systematize due to the variable responses that are likely with each unique individual. However, a 2017 article by Booth et al. (15) does offer some general guidelines that essentially boil down to, “start low and go slow” based on an individual’s specific goals.

Nevertheless, as you can see above, the authors do offer a solid framework to guide dosing and are the parameters I most often aim for when working with folks with persistent symptoms. For further reading, check out this article to help find a successful entry point to movement.

Moving Forward. Lifting with Persistent Pain

Overall, exercising with persistent pain can be a tricky endeavor. However, the juice will likely be extremely worth the squeeze for most folks who value training. Additionally, it can also be helpful to keep in mind that the benefits of exercise are likely much deeper than simply increasing strength, as Booth et al 2017 (15) discuss,

“In CLBP, improvements in pain and disability during an exercise programme were unrelated to changes in physical function. It follows then that other exercise‐induced changes in secondary pathologies, improved psychological status and cognitions (e.g. reduction in fear, anxiety and catastrophization, increased pain self‐efficacy), exercise‐induced analgesia, and functional and structural adaptions in the brain may influence pain and disability more than physical function.”

Booth et al go on to discuss that this is likely why specific exercise is not superior to general exercise in the research since the likely mediating factors for success (changes in pain and disability) involve the psychological and neurophysiological factors rather than the minutia of exercise with changes in strength, endurance and flexibility. Therefore, traditional parameters for strength, endurance, and flexibility are less relevant when working with those with persistent pain compared to the asymptomatic population.

Considering the multi-dimensional benefits of exercise, we have a ton of flexibility in dosing between the type, frequency, intensity and duration. In addition to pain management, numerous studies have also demonstrated other benefits involved with exercise such as preventing chronic disease, decreasing disability and overall optimizing systemic health (14, 15). Pairing a well dosed exercise program with PNE and ACT can provide us with the necessary understanding and flexibility to derive these benefits and persist with training by prioritizing willingness to engage in pain if the activity is adequately valued.

Once willingness and commitment are fully established, playing with dosage and managing flare ups can further help foster success throughout the journey of flexibly persisting through a weight lifting program with persistent pain!

References

- Cohen, S. P., Vase, L., & Hooten, W. M. (2021). Chronic pain: an update on burden, best practices, and new advances. The Lancet, 397(10289), 2082–2097. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(21)00393-7

- Warburton, D. E. R., & Bredin, S. S. D. (2017). Health benefits of physical activity. Current Opinion in Cardiology, 32(5), 541–556. doi:10.1097/hco.0000000000000437

- Geneen LJ, Moore RA, Clarke C, Martin D, Colvin LA, Smith BH. Physical activity and exercise for chronic pain in adults: an overview of Cochrane reviews. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;4:CD011279. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD011279.pub3.

- Meeus, M., Nijs, J., Van Wilgen, P., Noten, S., Goubert, D., & Huljnen, I. (2016). Moving on to movement in patients with chronic joint pain. Pain: Clinical Updates, 14, 1 .iasp.files.cms‐plus.com/AM/Images/PCU/ PCU%2024‐1.Meeus.WebFINAL.pdf

- Traeger AC, Lee H, Hübscher M, et al. Effect of Intensive Patient Education vs Placebo Patient Education on Outcomes in Patients With Acute Low Back Pain. A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Neurol. Published online November 05, 2018. doi:10.1001/jamaneurol.2018.3376

- Vowles, K. E., and Thompson, M. (2011). “Acceptance and commitment therapy for chronic pain,” in Mindfulness and Acceptance in Behavioral Medicine: Current Theory and Practice, ed. L. M. McCracken (Oakland, CA: New Harbinger Publications), 31–60.

- Smith BE, Hendrick P, Smith TO, et al. Should exercises be painful in the management of chronic musculoskeletal pain? A systematic review and meta-analysis Br J Sports Med. 2017; 51(23):1679-1687.

- Lennox Thompson, B., Gage, J., & Kirk, R. (2019). Living well with chronic pain: a classical grounded theory. Disability and Rehabilitation, 1–12. doi:10.1080/09638288.2018.1517195

- Kwon, M., Altin, M., Duenas, H., & Alev, L. (2013). The Role of Descending Inhibitory Pathways on Chronic Pain Modulation and Clinical Implications. Pain Practice, 14(7), 656–667. doi:10.1111/papr.12145

- Ossipov, Morimura. Descending pain modulation and chronicification of pain. Curr Opin Support Palliat Care. 2015;9(1):38-39. doi:10.1097/SPC.0000000000000055

- Ossipov MH. The Perception and Endogenous Modulation of Pain. Scientifica (Cairo). 2012;2012:1-25. doi:10.6064/2012/561761

- Polaski AM, Phelps AL, Kostek MC, Szucs KA, Kolber BJ. Exercise-induced hypoalgesia: A meta-analysis of exercise dosing for the treatment of chronic pain. PloS one. 2019; 14(1):e0210418.

- Andrade, A., de Azevedo Klumb Steffens, R., Sieczkowska, S.M. et al. A systematic review of the effects of strength training in patients with fibromyalgia: clinical outcomes and design considerations. Adv Rheumatol 58, 36 (2018). doi: 10.1186/s42358-018-0033-9

- Ellingson LD, Stegner AJ, Schwabacher IJ, Koltyn KF, Cook DB. Exercise strengthens central nervous system modulation of pain in fibromyalgia. Brain Sci. 2016;6(1):13. doi:10.3390/brainsci6010008

- Booth, J, Moseley, GL, Schiltenwolf, M, Cashin, A, Davies, M, Hübscher, M. Exercise for chronic musculoskeletal pain: A biopsychosocial approach. Musculoskeletal Care. 2017; 15: 413– 421. https://doi.org/10.1002/msc.1191

- Geneen LJ, Moore RA, Clarke C, Martin D, Colvin LA, Smith BH. Physical activity and exercise for chronic pain in adults: an overview of Cochrane Reviews. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017 Jan 14;1(1):CD011279. doi: 10.1002/14651858.

- Lewis GN, Rice DA, McNair PJ. Conditioned pain modulation in populations with chronic pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Pain 2012;13:936–44.

- Yarnitsky, D. (2010). Conditioned pain modulation (the diffuse noxious inhibitory control-like effect): its relevance for acute and chronic pain states. Current Opinion in Anaesthesiology, 23(5), 611–615. doi:10.1097/aco.0b013e32833c348b

- Geneen LJ, Moore RA, Clarke C, Martin D, Colvin LA, Smith BH. Physical activity and exercise for chronic pain in adults: an overview of Cochrane Reviews. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2017, Issue 4. Art. No.: CD011279. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD011279.pub3.

- Sluka KA, Frey-Law L, Hoeger Bement M. Exercise-induced pain and analgesia? Underlying mechanisms and clinical translation. Pain. 2018;159(9):S91-S97. doi:10.1097/j.pain.0000000000001235

- Da Silva Santos R, Galdino G. Endogenous systems involved in exercise-induced analgesia. J Physiol Pharmacol. 2018;69(1):3-13. doi:10.26402/jpp.2018.1.01

- Butler, D. S., & Moseley, G. L. (2003). Explain pain. Adelaide: Noigroup Publications.