At Barbell Rehab, we advocate using Rating of Perceived Exertion (RPE) to help guide loading decisions for athletes in the weight room. Originally developed by Gunnar Borg in the early 1970s as a way to measure the perceived exertion of aerobic exercise on a scale of 6-20, this has evolved into the 1-10 RPE scale we utilize today as a way to measure perceived exertion during resistance training.

While we believe that utilizing RPE is one of the best methods for gauging intensity during performance-based resistance training, it poses some limitations for clients dealing with pain:

- What if pain occurs at low exertion levels and thus low RPEs? Is RPE as useful in this scenario?

- RPE is based purely on exertional levels, not on one’s tolerance to the exercise. In the presence of pain, one’s tolerance level and exertional level may be vastly different.

In this article, we want to discuss a potentially better way to prescribe and gauge intensity during resistance training exercises for clients dealing with pain. We will first start with an overview of how RPE works, its benefits and limitations, and then put forth the concept of using Rating of Perceived Tolerance (RPT) instead of, or in conjunction with, RPE for clients dealing with pain.

The Basics of RPE

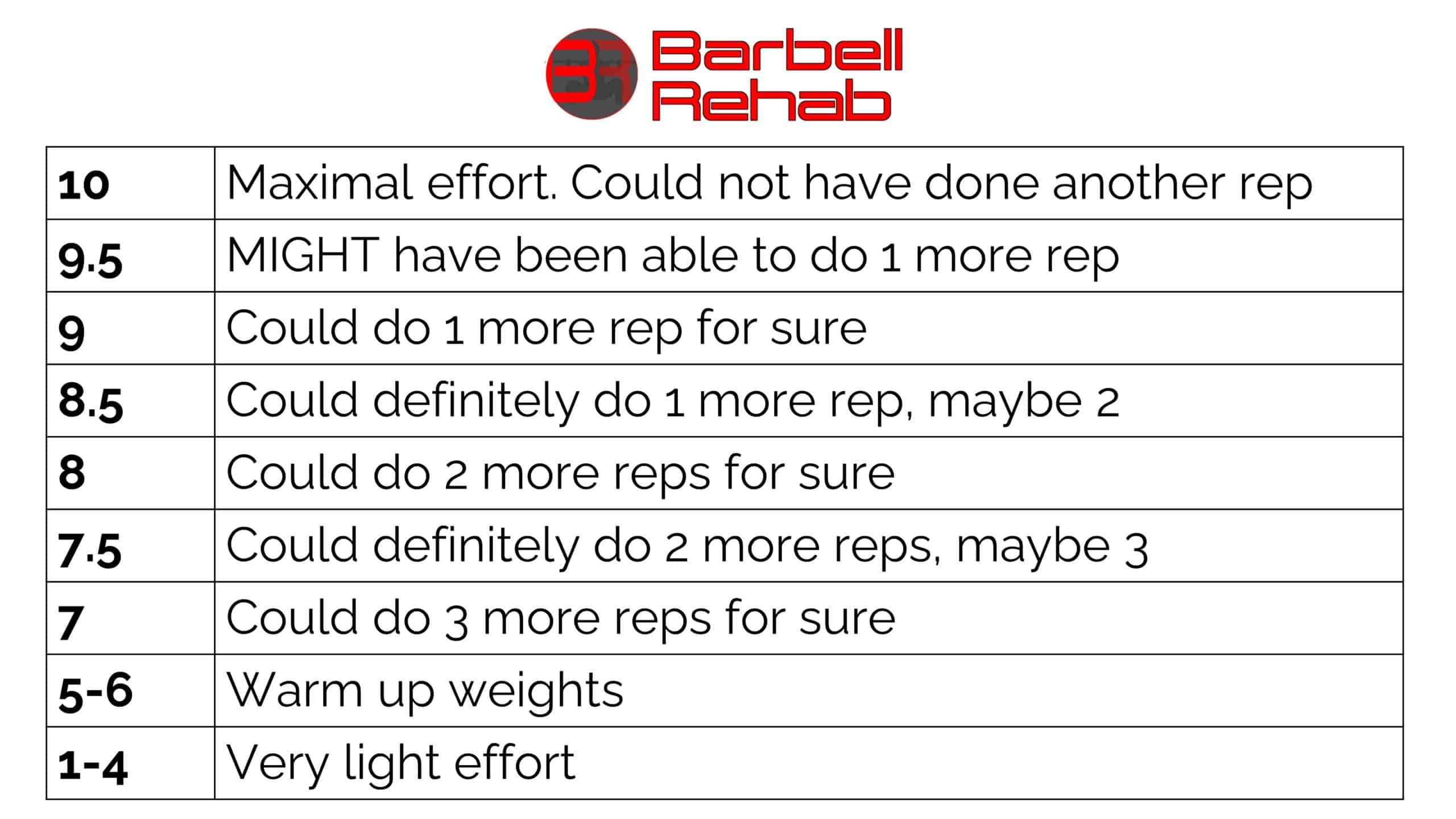

While resistance training, athletes usually provide RPEs on a set-to-set basis. After completing a set of an exercise, the athlete retroactively rates how difficult that set felt to them on a scale of 0-10. A rating of 10/10 would indicate that the set was truly maximal effort, meaning the athlete could not have completed another rep, even if they tried. A rating of 9/10 would indicate that the athlete stopped 1 rep shy of failure, a rating of 8/10 would indicate that they stopped 2 reps shy of failure, and so on and so forth. Check out the chart below for more details.

To further increase rating accuracy, increments of 0.5 can be implemented as well. For example, a rating of 8.5 means the lifter could have definitely done one more rep and maybe another one. For more information about RPE, check out this article here.

Using RPE for Performance Based Training

The main benefit of using RPE derives from the inherent variation in human performance on a day-to-day basis. Due to normal biological and psychological factors and variables such as sleep, nutrition, and life stress; an athlete’s “readiness for training” on any given day may be different.

Utilizing RPE can help to “autoregulate” the intensity of a lift based on readiness on that specific day. In other words, on days where the lifter may be more fatigued, RPEs will be slightly higher for a given load compared to days where the lifter is more prepared. This allows the lifter to essentially “push it” on days they feel good, and back off on days the bar is feeling heavy – the essence of autoregulation.

How to Utilize RPE During Training

Now that you know what RPE is and why we use it, let’s talk about how to use it. Contrary to popular belief, training the basic compound movements (squat, hinge, bench press, etc) to failure is NOT needed in order to stimulate growth and hypertrophy.

When training these movements, we recommend that the bulk of the working sets should be in the RPE 7-8.5 range. Consistently training at RPEs > 9.0 may make the client more susceptible to load management error and may increase injury risk.

In other words, leaving a few repetitions in reserve (RIR), or “reps in the tank”, is something we advocate for on the basic compound lifts, as it is a high enough relative intensity to stimulate progress, but not so high that you’re consistently and excessively straining and potentially missing lifts.

Limitations for Using RPE During Training

While we believe that utilizing RPE is one of the most effective and sustainable ways to dose resistance training intensity, it does have its limitations. First, let’s explain the tendency to overrate or underrate RPE.

For Beginners: Overrating RPE

In general, those that are new to training may have a tendency to overrate the intensity of the lift. Why? When someone is new to training, everything is going to feel difficult! As both a coach and physical therapist, I’ve seen this countless times. You may ask someone to perform a set of 4-6 reps on a barbell back squat, see no decrease in bar speed on the last rep, only for the trainee to report an RPE of 8-10..

Here’s the thing, everything feels difficult for someone new to training. Fortunately, with practice, the beginner lifter will learn how to more accurately use RPE. Just like anything, there is a learning curve. Furthermore, an occasional RPE check/audit can be used on the final set of an exercise, where the lifter is instructed to push to failure. This allows the lifter to retroactively assess their RPE on previous sets, providing information for future weeks of training.

Practically, this might look like a top set of 5 reps at RPE 7 followed by 3 back off sets of 5 reps with a weight that is 90-95% of the top set. An RPE rating would be given for each back off set. The third set would be marked a 5+, meaning that the lifter would push until fatigue. The number of reps associated with this set (RPE 10) would help to retroactively assess the RPE rating ability of the first and second back off sets.

For the Advanced: Underrating RPE

While beginners may have a tendency to overrate RPE, more experienced lifters may tend to underrate their RPE, especially on sub-maximal sets (1). For example, Hackett et al had experienced bodybuilders perform 5 sets of 10 reps of both the bench press and squat. All sets were completed with the same load (70% of their 1RM) and participants were asked to estimate how many more reps they could complete before failure on each set. Guess what they found? All participants tended to significantly underrate the amount of reps to failure on the first set, but as the sets progressed and fatigue set in, their estimate of reps to failure (and essentially RPE) significantly improved (2).

Said differently, it can be difficult to accurately rate RPE when sets are submaximal.

On the contrary, Helms et al. were able to demonstrate that RPE targets can be effectively utilized for exercise prescription in powerlifters, especially when the repetitions utilized are low/moderate (2-8 repetitions) and the proximity to failure is low (8-9 RPE). In this study, the mean range of error for rating RPE was only 0.22-0.44, well within a range that the authors considered to be useful (3).

Now that you know that RPE accuracy essentially increases the closer to failure the lifter reaches, let’s add another variable into the equation… pain.

Using RPE in Clinical Practice and for Clients with Pain

Teaching others how to manage pain during training is our specialty (hence the whole “Barbell Rehab” thing). In regard to pain during training, there are many variables you can manipulate in order to make it more tolerable. If this is your first time reading something from us, I’d highly recommend that you check out out our free e-book A 4-Step Framework for Training with Pain as it outlines, in detail, our general approach to this.

One variable that we tend to focus on for those with pain is exercise intensity. While there is no clear-cut answer for what the “optimal” exercise intensity for someone in pain should be, “start low and go slow” is both a practical strategy and what we recommend.

Whether you’re working with someone who is dealing with persistent pain, or re-integrating a once painful lift into someone’s program; prescribing initial working sets in the RPE 3-4 range is a reasonable strategy. Starting at such a low intensity can allow the client to achieve “small wins” in the beginning (consistent and frequent tolerable training sessions) and help to reframe the exercise as a positive stimulus for them as opposed to a noxious one. This concept is something that we teach extensively about in both our online and live CEU approved courses.

While we currently believe this is the best approach for optimizing intensity and long-term progress in this clientele, it has two major downsides:

- As mentioned above, RPE can be difficult to accurately measure at submaximal weights, especially at the extremely low RPEs of 3-4 that we recommend as the entry point for training with pain.

- In the presence of pain, there is often a mismatch between the client’s “exertion” and “tolerability” to exercise.

Let’s dig into this a little more.

The Difference Between Exercise Tolerance and Level of Exertion

A few years ago, I was dealing with shoulder pain during the dumbbell bench press. It caught my attention that I felt really “strong” with this movement, but was having pain with lighter loads. This is a common finding in other lifters experiencing pain during training.

While everyone’s pain tolerance will differ on a pain scale of 0-10 (0 = no pain and 10 = worst pain imaginable), generally pain of 3-4/10 is considered tolerable while pain levels of 5 or above may be considered intolerable. In my situation, I was experiencing greater than 5/10 pain at low levels of exertion (low RPE). I knew I could have easily worked up to 80lb DBs in terms of exertion, however, the pain would have most likely been quite intolerable (>8/10 in that situation).

Overall, what I was experiencing was a mismatch between tolerability and exertion. In other words, I had low tolerability for the exercise even at low exertion levels. And this is exactly where the concept of setting the intensity at RPE 3-4 essentially weakens. When we dose exercise for those in pain based purely on exertion, it doesn’t take into account those who have low tolerability at low exertion levels. This may lead to RPEs as low as 3-4 that are at or above someone’s tolerance threshold and thus not very useful for prescribing exercise for those in pain.

What if there was a way to prescribe exercise for those in pain based on an individual’s tolerance to the movement vs. their actual physical exertion during the movement?

Let’s introduce the concept of Rating of Perceived Tolerance (RPT).

Using Rating of Perceived Exertion (RPT) Instead of Rating of Perceived Exertion (RPE)

While I’m sure there are many clinicians and coaches prescribing exercise for clients in pain based on tolerance, to my knowledge, we have yet to conceptualize a true scale to measure this. A quick search on PubMed reveals no prior articles on the concept of “Rating of Perceived Tolerance” or “RPT” so I’m going to introduce it here.

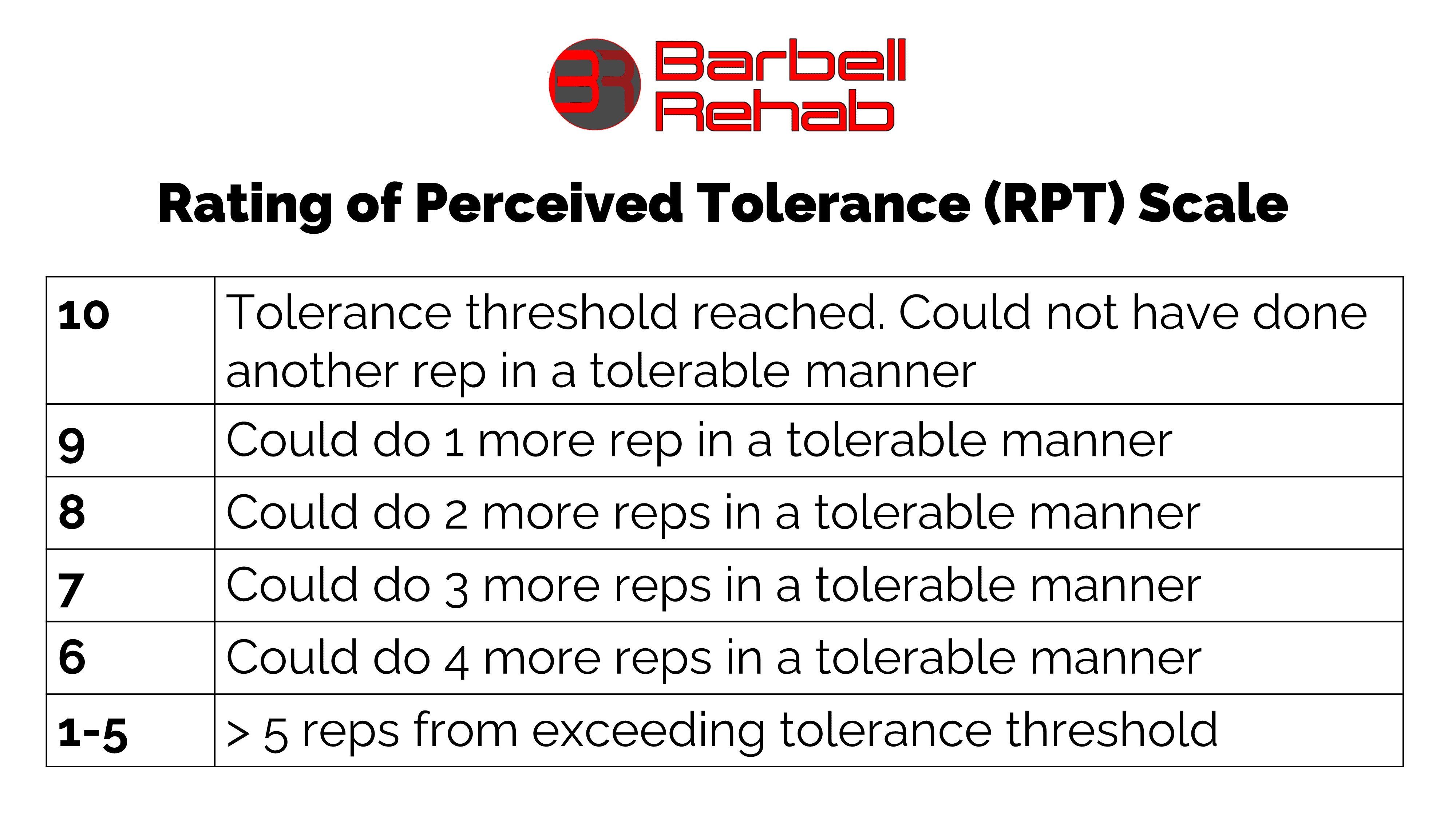

While Rating of Perceived Exertion (RPE) is used to identify the subjective effort put forth by the trainee during strength training, Rating of Perceived Tolerance (RPT) can be used to identify how tolerable an exercise feels at a given load.

Another way to explain it would be as follows: If a client completes a set of squats and retroactively rates that set an RPE of 10/10, this would imply that the set was performed at maximal effort and that no more reps could have been completed even if the client tried (in other words, they’ve reached their exertional threshold). On the other hand, if the client reported a Rating of Perceived Tolerance (RPT) of 10/10 on this set of squats, this would imply that the trainee reached their tolerance threshold, and that no more reps could be completed in a tolerable fashion.

With an RPT of 10/10, while more reps might have been able to be completed from an exertional standpoint, continuing to complete additional reps would exceed the tolerance threshold, and not be something we’d advise in most situations. Understanding this, we now propose the Rating of Perceived Tolerance (RPT) Scale:

The Relationship between RPE and RPT

Now that we’ve defined RPT, let’s dig a little further into how it can correlate with RPE. In order to really explain this, I’m going to give three different scenarios. One where RPE and RPT would be identical, one where they would be slightly different, and one where they would be very different.

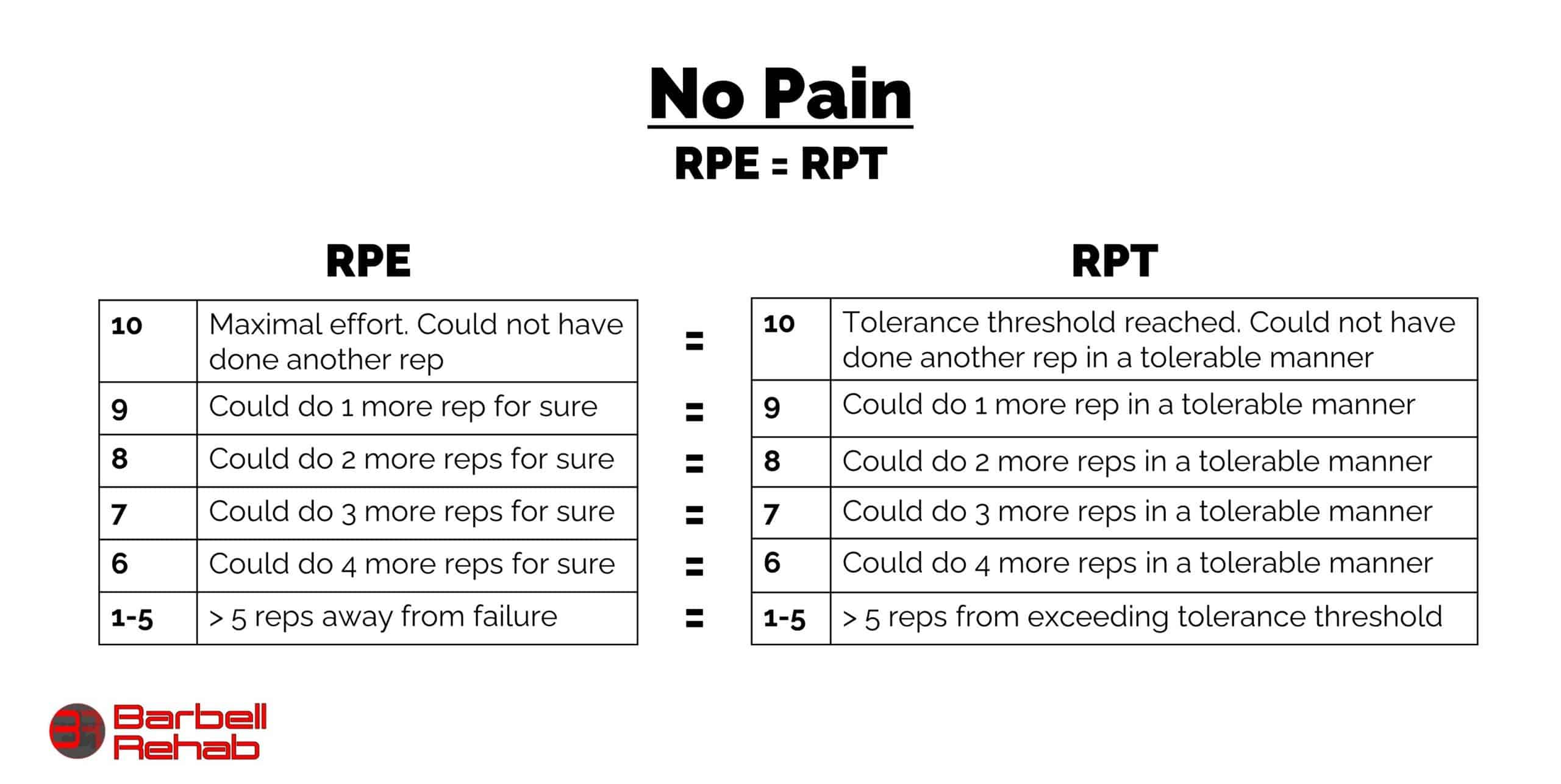

Scenario 1: Client has no pain. RPE = RPT

In this scenario, let’s take someone who has no pain. In this case, the RPT would equal the RPE, as the tolerance and exertional threshold would be the same. In other words, the client has no pain even when taking their sets to exertional failure. In this case, I wouldn’t even use RPT, as RPE would suffice when it comes to programming decisions. This is the situation in most performance-based training.

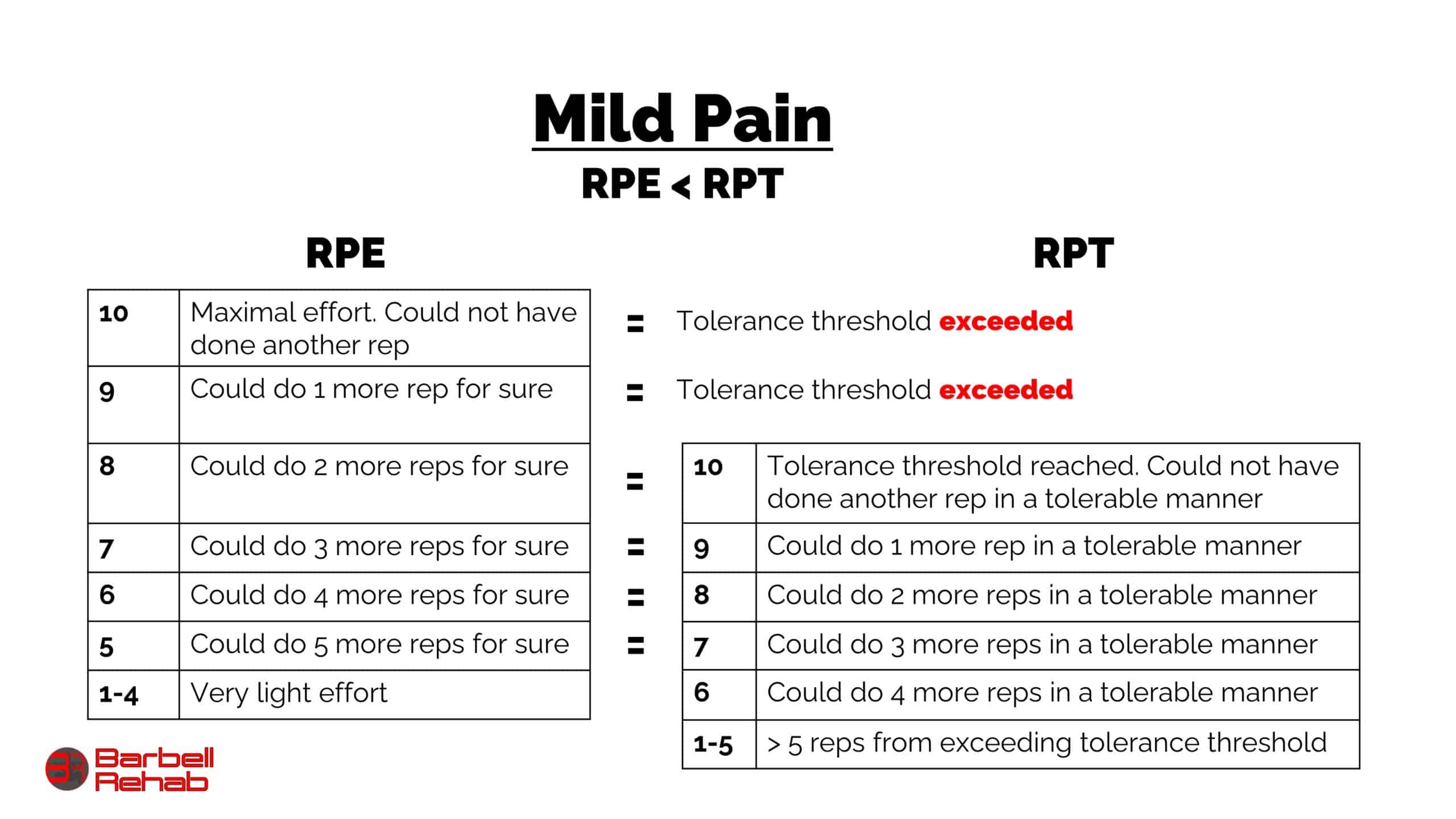

Scenario 2: Client has mild pain. RPT > RPE

In this second scenario, let’s take someone who is dealing with low level persistent pain. In this case, the reported RPTs may be slightly higher than RPEs at a given load. For example, let’s say someone is dealing with persistent knee pain during squats. In this example, let’s assume they are able to achieve an RPE 10/10 but training starts to become intolerable at RPE 8/10.

In other words, RPEs of 9-10/10 exceed their tolerance threshold (meaning that the pain is probably > 4/10 on the VAS scale starting at RPE 8). Since training becomes intolerable at RPE 8/10, this RPE 8/10 would equal an RPT of 10/10. For this client, utilizing the RPT scale could be useful, as you could prescribe loads at the 7-8/10 RPT range (meaning the client would stop their sets 2-3 reps shy of their tolerance threshold) instead of training at an RPE range of 5-6/10.

Knowing that it can be difficult to accurately select RPEs for submaximal sets, we hypothesize that, in this scenario, selecting load and intensity based on RPT might lead to more accurate and sustainable loading decisions.

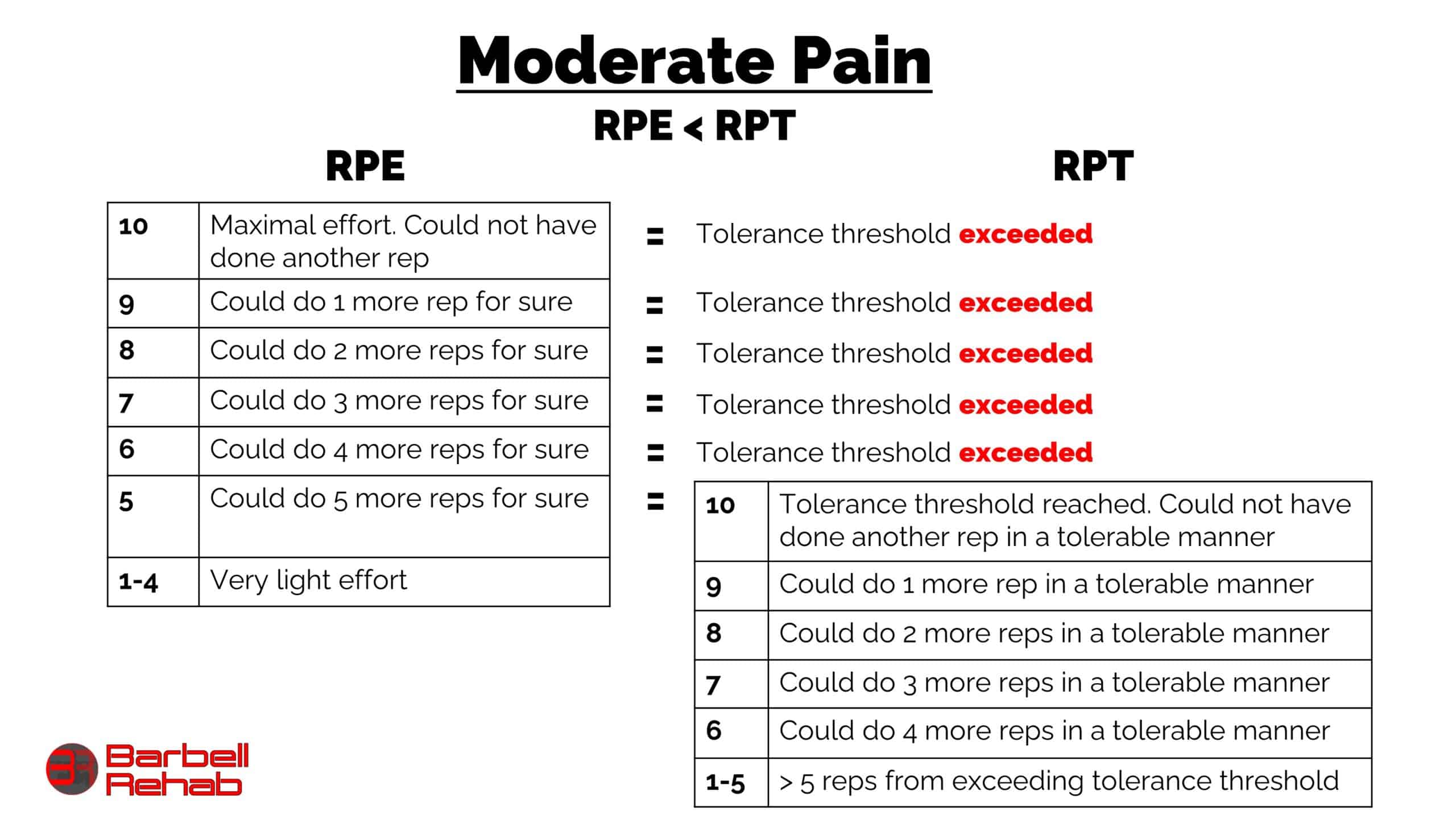

Scenario 3: Client has moderate pain. RPT > RPE

In this last scenario, let’s use the example of someone who is a little more sensitized to a particular movement than scenario 2. In this case, pain during a lift becomes intolerable at the 5/10 RPE range. In other words, the client is sensitized even at lighter loads and an RPE of 5 would equal an RPT of 10.

If we prescribed exercise in this situation based on RPE, we’d have to dose it in the RPE 3-4 range to make the exercise tolerable. And knowing that low RPEs can be difficult to really rate, we hypothesize that reframing the exercise and training in the RPT 7-8/10 range would be more accurate than prescribing it in the RPE 3-4 range.

As you can see, the more sensitized to a movement an individual is, the larger the difference between the RPE and RPT. In other words, the tolerance threshold is far below the client’s exertional threshold. In cases like this, where there is a large difference between RPE and RPT, we hypothesize that prescribing exercise using RPT could be really beneficial. As the client progresses, RPT will get closer to RPE until they eventually equal, at which point we’d use solely RPE during training instead of RPE.

Utilizing Rate of Perceived Tolerance (RPT) in Clinical Practice

Now that we’ve introduced the concept of RPT and how it relates to RPE in different situations, let’s talk about how to utilize it to prescribe exercise for those in pain. As mentioned above in scenario 3, we believe that using RPT to prescribe exercise could be really beneficial when there is a large difference between one’s exertional threshold and one’s tolerance threshold. So, let’s use that as an example here.

Let’s say you’re working with a client who is experiencing back pain during her deadlift. Rather than trying to prescribe an RPE of 3-4/10, we can prescribe it at an RPT of 7/10. In other words, we want this client to perform her working sets about 3-4 reps shy of her tolerance threshold. How do we accomplish this?

First, select the rep range you want her to work in. This is a clinical decision that will be based on the client’s goals and the adaptation you’re trying to achieve. We’d recommend lower reps (4-6) for those who are exercise intolerant, those who may display high fear avoidance or anxiety of the movement, and those whose goal is to eventually perform at higher intensities in the lower rep ranges. We’d recommend higher reps (6-12) if the goal is to build tolerance to higher rep ranges or a case of tendinopathy.

Once you know the rep range that you want her to work in, providing some education and setting expectations for the session would be advised. Let this patient know that a little bit of pain during the exercise is ok provided that it is “tolerable.” The next logical question the client may ask is “what do you mean by tolerable” and you would let her know that “tolerable” means up to 3-4/10 pain on a pain scale of 0-10, or considered mild.

Next, let her know that you’re going to have her perform multiple sets of this exercise at the same rep range, while slowly increasing the weight on the bar every set. Then, ask her to let you know how she feels after each set – whether there is pain or not, and whether it is tolerable or not.

Once the client reports pain during a set, you can:

- Ask her to rate it on a scale of 1-10

- Ask her how many reps she could have done before the pain became intolerable

Based on her answers from the above 2 questions, you’ll be able to determine the Rating of Perceived Tolerance (RPT).

When using the RPE scale for clients with pain, our recommendation is to work up to 2-3 sets of RPE 3-4/10 on Day 1. In accordance with the concept of “start low and go slow” we’d rather undershoot it than overshoot it initially. It should be noted that sometimes the initial intensity entry point during rehabilitation is even lower than RPE 3-4, which is just another reason why RPT could be helpful. However, because we are using RPT in this scenario, we’d recommend having the client work up to an RPT 7-8. In other words, we want them to stop 2-3 reps short of their tolerance threshold on the first day.

As mentioned above, by prescribing the intensity based off of a tolerance threshold instead of an absolute exertional threshold, we believe that this will lead to more sustainable dosing decisions.

Here’s what the deadlift loading scheme for this client may look like on Day 1:

- Set 1: 6 reps @ 65lbs. No pain

- Set 2: 6 reps @ 85 lbs. No pain

- Set 3: 6 reps @ 95lbs. Mild 1/10 pain. Notes that she’s just starting to “feel it” and that she could have done at least 5-6 more reps before it really started bothering her. (RPT 4-5/10)

- Set 4: 6 reps @ 105lbs. Mild 3/10 pain. Notes that she could have done 3 more before it really started bothering her. (RPT = 7)

- Set 5: (Repeat from above) 6 reps @ 105lbs. Mild 4/10 pain. Notes that she could have done 2 more reps before it really started to bother her (RPT = 8). This is the last set of this exercise for this day.

The scenario above would be a perfect example of how to use Rate of Perceived Tolerance (RPT) in the clinic. The client may have been working significantly under her exertional threshold, making RPE far less reliable than RPT in this situation.

Potential Limitations of Using RPT in Clinical Practice

As with anything in the fitness and rehab industry, no model or concept is perfect. Here are some potential limitations we envision with using Rating of Perceived Tolerance (RPT)

It’s another scale to learn. As with any new concept, we assume there will be a learning curve for both the clinician and client. If the client is totally new to the concept of autoregulation, teaching him or her both the RPE scale and RPT scale and their relationship to one another on Day 1 could be overwhelming. As you see in the example above though, we may not necessarily “need” to teach the client the RPT scale in order to get the job done though. Using questions like “how many more reps do you think you could do in a tolerable fashion” instead of lecturing them about RPT could reduce this information overload.

There might still be a tendency to over or undershoot rating. Just like RPE, we anticipate the people will also both overshoot and undershoot RPT. Folks that tend to avoid pain the second they feel it may tend to overrate the RPT in the early stages, and those that are always pushing through pain may tend to overrate it. That’s ok though. We understand and accept this learning curve.

As you can see, there certainly are some barriers and pitfalls to the concept of Rating of Perceived Tolerance (RPT); however, we really do believe that it could help gauge the intensity of resistance training more effectively for people dealing with pain.

Final Thoughts and RPT Summary

While utilizing the RPE scale as a guide for loading decisions for performance-based training is one of the best autoregulation methods we have out there, using it for the reconditioning or rehabilitative process has some downsides. As mentioned, one main pitfall of RPE is the lack of ability to accurately rate how difficult a set feels at submaximal intensities, and these are the intensities that are used quite frequently in the early rehabilitation stages.

We propose that using Rating of Perceived Tolerance (RPT) instead of Rating of Perceived Exertion (RPE) in the early stages of rehabilitation could lead to more accurate intensity prescriptions, as the clients will now be reframing the exercise based on their tolerance to it rather than their true physical exertion levels. As the client progresses along the spectrum from rehab to performance, and their tolerance level increases, gradually shifting from using RPT to RPE would be appropriate.

While the evidence is certainly mixed on “what is the optimal exercise intensity for clients in pain,” utilizing the Rating of Perceived Tolerance (RPT) scale could be a step in the right direction in making more accurate loading decisions for this population.

References

- Helms ER, Cronin J, Storey A, Zourdos MC. Application of the repetitions in reserve-based rating of perceived exertion scale for resistance training. Strength Cond J. 2016;38(4):42-49.

- Hackett DA, Johnson NA, Halaki M, and Chow CM. A novel scale to assess resistance-exercise effort. J Sports Sci 30: 1405–1413, 2012.

- Helms, Eric R, Brown, Scott R, Cross, Matt R, Storey, Adam, Cronin, John, and Zourdos, Michael C. “Self-Rated Accuracy of Rating of Perceived Exertion-Based Load Prescription in Powerlifters.” Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research 31.10 (2017): 2938-943. Web.